Paris, late June, 1914

“….It was a perfect summer day; brightly dressed groups were gathered at tea tables beneath the overhanding boughts, or walking up and down the flower-bordered turf….Outside in the quiet street stood a long line of motors, and on the lawn and about the tea-tables there was a happy stir of talk… I joined a party at one of the tables, and as we sat there a cloud-shadow swept over us, abruptly darkening bright flowers and birght dresses. “Haven’t you heard? The Archduke Ferdinand assassinated…at Sarajevo…where is Sarajevo? His wife was with him. What was her name? Both shot dead.”

A momentary shiver ran through the company. But to most of us the Archduke Ferdinand was no more than a name…”

—Edith Wharton, from her memoir A Backward Glance

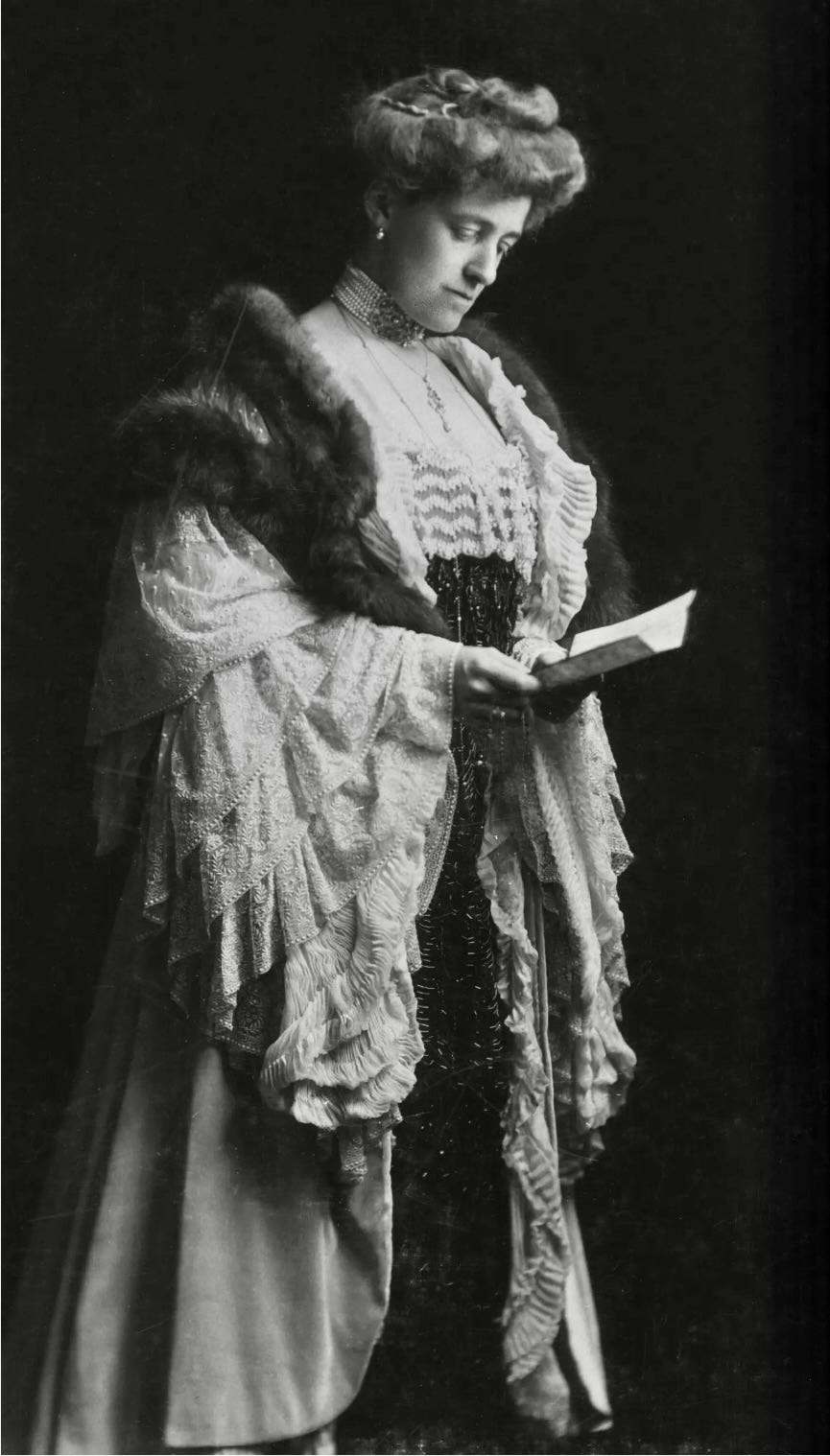

This is how Edith Wharton recalled the moment she learned about the inciting incident of the Great War, as they called it. In her memoir A Backward Glance, she wrote of her own ignorance, and the ignorance of her artist, writer, and even diplomat friends, about what this incident would lead to. A few years earlier, nearing age 50, Wharton had moved to France to find a new, more literary life after her marriage to Teddy Wharton broke down. Now she was happily ensconced in Paris, in a rented apartment on the Rue de Varenne, on the Left Bank.

(Part one of my post about Edith Wharton at midlife, and the country house where she wrote her first novels, is linked below.)

That year, 1914, Wharton had planned to rent a house in England for the fall, to write and to host her English and American-expat friends like Henry James, Howard Sturgis, and Mary Hunter. In late June, she closed her Paris apartment and sent her servants ahead to England (as one does, if one is a privileged American, one whose novels have added to one’s fortune), while she traveled with friends in Spain, wandering through Barcelona, then to the Pyrenees and Bilbao looking for cooler weather. At the end of July, she returned to Paris, “where the air was already thick with rumors. Everything seemed strange, ominous and unreal, like the yellow glare which precedes a storm.”

When war was declared, Wharton found herself with no money—the banks wouldn’t release funds to anyone—and no way to get to England or to pay her servants for their work in the English house. She finally retrieved $500 from New York by agreeing to pay $500 for the transaction, and her friends advised her to go to England, as they were doing, and to stay there “‘till the war was over,’ that is, presumably, sometime in October,” she wrote.

While Wharton waited in Paris for a permit to go to England, her friend the Comtesse d’Hussonville, who served as President of the Red Cross in Paris, asked her for a big favor: to organize a workroom for the women in their arrondissement who were waiting for government assistance. Everything—hotels, restaurants, workrooms—had closed down as the men went off to war, and women and children all over Paris had no income from their husbands, and no way to make money on their own.

“I was totally inexperienced in every form of relief work, and not least in the management of anything like a work room for seamstresses and lingères; and I had no money to do it with,” Wharton wrote. Even so, she found a big empty apartment nearby, drew on her own funds a little as a time, as French banks were beginning to allow. And then: “I assailed all my American friends who were either living in Paris or stranded there,” and collected twelve thousand francs. Soon, she was in charge of 90 women seamstresses. She decided that these seamstresses could make lingerie instead of hospital supplies, and once again, she badgered (her word) her friends to order lingerie and other items, building “a thriving trade in unexpected lines, including men’s shirts (in the low-neck Byronic style) for young American artists from Montparnasse!”

I was totally inexperienced in every form of relief work, and not least in the management of anything like a work room for seamstresses and lingères; and I had no money to do it with.

Meanwhile, as the Germans advanced, Paris filled with Belgian and French refugees, and since the Red Cross was overwhelmed with field duties, Wharton was again asked to help out. This time she formed a committee to raise money for the refugees, and to do the more hands-on work of feeding, clothing, and resettling the refugees. She raised more money, helped create a system and departments, and dug in to the work of getting the refugees registered and meeting their basic needs. She also recruited many more volunteers, including a who’s who of artistic Paris (André Gide, Percy Lubbock, Darius Milhaud), too.

I love how she described the difficulty of figuring out which volunteers she could count on, and which she couldn’t. “Some would drift in vaguely, saying…’don’t expect too much from me,’ and would turn out to be the future cornerstones of the building. Others, lucid, precise, and self-confident, would point out our deficiencies, offer to remedy them, and fade away after a week.” If you’ve ever been part of a volunteer effort, doesn’t this ring true?

Before long, Wharton was essentially presiding over an enormous endeavor, and she continued to raise money throughout the war for refugees and working-class women and children. By the end of the war, Wharton and her committee had cared for 5000 refugees, and had built care homes for old people and children, along with four tuberculosis hospitals for women and children.

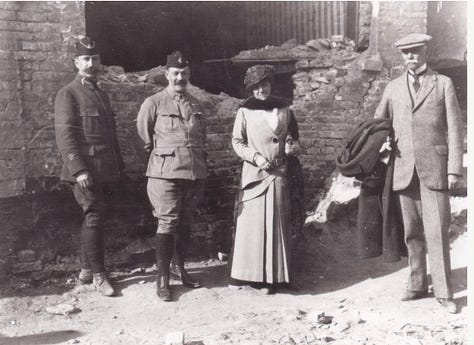

During the war, Wharton also visited the French front multiple times, invited by the Red Cross, and she reported on the needs of military hospitals in articles for American magazines, and she pushed for the US to join the war. She also created a fundraiser of a book, The Book of the Homeless, soliciting entries from that era’s literary and artistic luminaries (Yeats, Monet, Henry James, Sarah Bernhardt, Sargent, Renoir, Rodin, and on and on), and raising still more money for refugees. After the war, the French government made her an officer of the Legion of Honor, its highest honor, for her service to France.

Wharton wrote that the end of the war brought a brief feeling of rapture, followed by a growing sense of the waste and loss of those years. “Death and mourning darkened the houses of all my friends, and mingled my private grief with the general sorrow,” she wrote, noting all the friends and relatives who’d died in the war, along with the death of her friends Howard Sturgis and Henry James, “the perfect friend of so many years…”

I was already in the clutches of an inexorable calling, and though individual cases of distress appeal to me strongly, I am conscious of lukewarmness in regard to organized beneficence. Everything I did during the war in the way of charitable work was forced on me by the necessities of the hour, but always with the sense that others would have done it far better, and my first respite came when I felt free to return to my own work.

Wharton also could have written that her war work was an honor of a lifetime, or some other humble-brag. Instead, she wrote this:

“Many women with whom I was in contact during the war…found their vocation in nursing the wounded, or in other philanthropic activities. The call on their cooperation had developed unexpected aptitudes which, in some cases, turned them forever from a life of discontented idling, and made them into happy people. Some developed a real genius for organization, and a passion for self-sacrifice that made all selfish pleasures appear insipid. I cannot honestly say that I was of that number. I was already in the clutches of an inexorable calling, and though individual cases of distress appeal to me strongly, I am conscious of lukewarmness in regard to organized beneficence. Everything I did during the war in the way of charitable work was forced on me by the necessities of the hour, but always with the sense that others would have done it far better, and my first respite came when I felt free to return to my own work.”

As to that work of her own, Wharton wrote little fiction during those long war years, other than a short novel, Summer, and at war’s end, a novella, The Marne, which sold poorly, probably because people had had enough war stories.

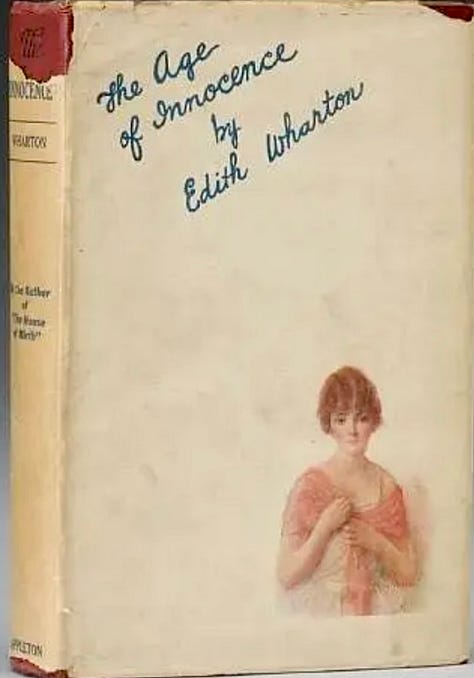

But after the war, Wharton left Paris for a suburban house north of the city, and began to write The Age of Innocence. It’s the novel she’s probably best known for. It won the Pulitzer Prize and it’s still read today.

It’s possible that she could have written The Age of Innocence if the war had never happened. But it seems to me that work, the strain, and the grimness of the war years, along with the deaths of two of her best friends, Henry James and Howard Sturgis, might well have led her to write a looking-back kind of novel. The Age of Innocence is set in 1870s New York City, in the era of Wharton’s girlhood. By 1920, that world—privileged, WASPy, rigid, constrained—was long gone. It was also a world she deliberately left behind. And yet after the war, maybe she longed for it, a little.

Further reading:

A Backward Glance, Edith Wharton, originally published 1933; Touchstone, 1998.

Henry James and Edith Wharton, Letters: 1900-1915, Lyall Powers, editor, Scribner, 1990.

“Dearest Edith,” Janet Flanner, 1929, The New Yorker, Janet Flanner’s snarky yet admiring piece about Edith Wharton.

A great glimpse at the good and unexpected work some women found to do. I especially love this quote:

“The call on their cooperation had developed unexpected aptitudes which, in some cases, turned them forever from a life of discontented idling, and made them into happy people. Some developed a real genius for organization, and a passion for self-sacrifice that made all selfish pleasures appear insipid.”

I love her self-honesty about not enjoying her rise to the occasion of the war, and missing her friends and her private imaginative space. Many can relate to this.