Last week I went with my daughters to see the John Singer Sargent exhibit, Fashioned by Sargent, at the MFA Boston. (If you’re in New England and at all interested, go soon—it closes January 15.) It’s a beautiful show, a joint effort with Tate Britain, looking at Sargent’s relationship with portrait painting, his clients, and their clothes. It’s organized thematically, a large show with 50 portraits over multiple galleries, along with period dresses and costumes, like Ellen Terry’s Lady MacBeth dress that was embellished with thousands of iridescent Japanese beetle wings.

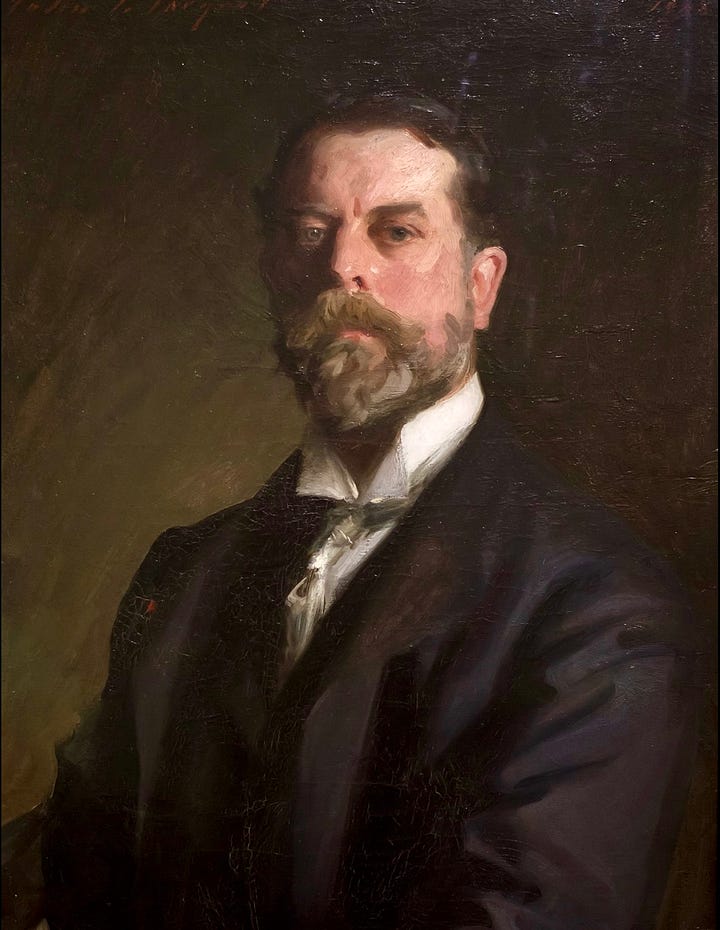

One of my favorite Sargent portraits, Lady Agnew of Lochnaw (below), is a focal point for the show.

(NB: If you’re reading this newsletter as an email, it may get clipped. You can read the full post here.)

Though I’d only seen some of these portraits in person, walking through the exhibit felt like being uncomfortably back with old friends. Uncomfortable because I spent almost seven years working on a novel about Sargent and his sister Emily, who was an artist too—in any other family she’d be considered the remarkably talented child. I first got entranced with the Sargent family at another exhibit: this one at the Corcoran Gallery in DC in 2009, a show about Sargent and his sisters’ childhood and their growing-up years abroad. The Sargent parents left Philadelphia for Europe after their first child died as a toddler, and they never returned to the US. All three Sargent children, John, Emily, and Violet, were born in Europe (John in Florence) and none of them ever lived in the US, except for visits to family or the months when John painted his murals for the Boston Public Library and at the MFA.

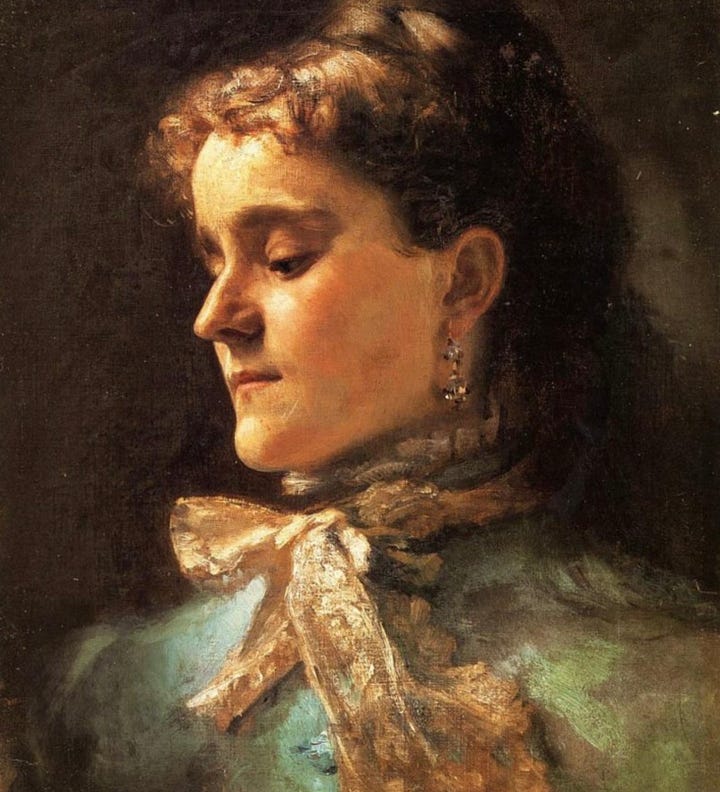

As I got to know John’s work, I couldn’t get over his incredible artistic facility from a young age and the immediacy of his portraits. And after that, I became entranced with Emily, who was crippled from a childhood bout of spinal tuberculosis—she wasn’t beautiful or glamorous, and was probably very shy, as John was, in her youth. But she too had a ton of facility with the paintbrush, though she never got to study with Parisian masters the way John did.

John supported Emily financially, and she supported him emotionally. Neither ever married; many scholars assume John was gay or bisexual. I suspect Henry James fell in love with John when John was a young artist in Paris. After John exhibited the scandalous portrait of the young socialite (and American expat) Madame Gautreau, Madame X, which wrecked his reputation for a while, Henry James persuaded John to leave Paris for London, and that is where John, Emily, their sister Violet, and their mother lived for the rest of their lives. I was also fascinated by the way John gave up his incredibly lucrative portraiture business at 50—he was a celebrity in his own right, but he was also sick of dealing with his wealthy, mostly British clients, and sick of making portraits. I wondered how Emily, who had little power in her own life, dealt with all of that. (I imagine that Emily may have been gay too; she had a longtime close friend and traveling companion, Eliza Wedgwood. Though of course that’s 21st-century speculation. As it’s only speculation about John.)

As I got to know John’s work, I couldn’t get over his incredible artistic facility from a young age and the immediacy of his portraits. And after that, I became entranced with Emily, who was crippled from a childhood bout of spinal tuberculosis—she wasn’t beautiful or glamorous, and in her youth was probably very shy, as John was. But she too had a ton of facility with the paintbrush, though she never got to study with Parisian masters the way John did.

John and Emily were at once insiders and outsiders—John, like Henry James, was constantly in demand for London hostesses’ dinner parties and house parties, and he dealt with aristocratic types every day. But John and Emily were also Americans with perfect French accents but weird, not-quite-American accents, and forever rootless. I think John identified with other insider/outsiders, like Henry James, and like the Wertheimer siblings (the wealthy grown children of art dealer Asher Wertheimer, who were Jewish in England, and not fully accepted by England’s upper-crust types).

Anyway, I researched and wrote, spending a lot of time with Emily and John and their artwork, and with the writings and letters and artwork of their friends, Henry James, Vernon Lee, Claude Monet, and others. I wrote, revised, listened to feedback from writing groups and workshops, went to London and France to get a sense of their world. Went to lectures about Sargent and interviewed his great-nephew, curator and art scholar Richard Ormond. Revised. Revised some more.

The novel that I finished in 2015, And Also Emily, His Sister, landed me an agent (who’s still my agent). But ultimately that novel never sold. The editors’ rejections were very complimentary, but the general word was “too quiet.” Too quiet is editor-speak for not propulsive or hooky enough.

While I was querying agents and while this novel was out on submission, I wrote a very different novel, one set in 1970, which turned into The Wrong Kind of Woman, which did get published. Since then I’ve worked on three other novel manuscripts, none of which are finished. But meanwhile I have all this no-longer-needed knowledge about Emily Sargent and John Singer Sargent. For instance, that Lady Agnew, pictured above, one of John’s first English clients, had her sittings interrupted by a bad case of the flu. She’s sitting in that chair, leaning back, with that confident, appraising gaze, in part because she’s still sick. Likewise, the 28-year-old artist and friend Graham Robertson was also getting over the flu when Sargent painted him, and if you think he looks a little ill, that’s why. (It sounds like I have a fixation on Edwardians with the flu…)

So back to last week, and the MFA exhibit. As my daughters and I looked at the portraits, I talked (lectured) more than I should have about John and Emily, and John’s portraits, stopping to tell them what what John or Emily said about a particular portrait or the sitter. About the incredible loose brushwork he used to indicate light, shine, transparent lace. About John’s love for Velazquez, Hals, and Balzac, and John’s and Emily’s musicality, their talent at the piano. How John essentially created British demand for his old friend Claude Monet. How Emily shied away from exhibiting her work because of her famous last name. About the kinds of pictures John and Emily liked to make later in life, almost abstract watercolor sketches. How quickly John’s work fell out of fashion after his death in 1925, not to be revived until the ‘80s, when curators and critics started looking at his work again.

For the last week or so, as I did in years past, I’ve been thinking about their lives as artists, how John and Emily kept making things, making pictures, for the rest of their lives, often while traveling—sketches of their friends, those abstracted watercolor landscapes. My novel will probably never see the light of day, but I learned a lot from Emily and John, about how to live a meaningful creative life, whether shadowed by a famous-artist brother, as Emily was, or bound and restricted by artistic fame, as John was. And not least, as I wrote about Emily and John, I also learned how to write a novel. ✍️

I would have paid to have you been my tour guide! I just finished the WRONG KIND of WOMAN and hope the Sargent Siblings is published. You are a wonderful writer and, I suspect, tour guide.

I LOVE quiet books and so do many people. So frustrating. I loved this post.