Leaving my home country behind to find myself: A Midlife Author interview with Linda Murphy Marshall

Plus a giveaway!

When you’re a midlife writer, you have a better idea of who you are and what you want, and you also realize you don’t have decades at your disposal to futz around and figure things out. You need to move ahead now, because you realize how short life is, and you know not to worry about what other people are saying or doing; you follow your own path.

—Linda Murphy Marshall

Hi friends! I’m excited to share this month’s Midlife Author Q and A, with linguist Linda Murphy Marshall, who’s made writing her second act. Memoir readers and writers, this one’s for you.

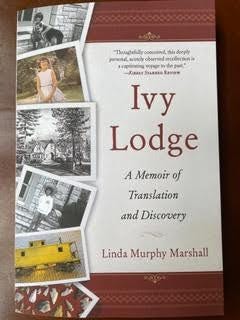

Linda is a multi-linguist and writer with a Ph.D. in Hispanic Languages and Literature from St. Louis University, and her writing has been published in The Los Angeles Review, The Catamaran Literary Reader, The Ocotillo Review, Maryland Literary Review, Brevity’s Nonfiction Blog, and Dorothy Parker’s Ashes. She’s spoken at Maryland Writers’ Association, American University, and Rice University. She’s also a docent at the Library of Congress and an associate at the National Museum of Language, and she’s served as translation editor at The Los Angeles Review. She is the author of two memoirs, Ivy Lodge and Immersion.

Hello, Linda! Where/when did you notice the first glimmers of writing? Or to put it another way, when did writing start calling to you more insistently?

I started writing poetry in my early teens, and when JFK was assassinated in 1963, I found it was the only way I could express my feelings. Since then, I’ve written 300+ poems, usually because they allowed me to express the inexpressible. Eventually, I added short stories and essays to my repertoire, and then my two memoirs, beginning in 2014 when I started to write Ivy Lodge.

You’re a linguist and translator, and a specialist in African languages; how has this word-related work informed your writing?

Foreign languages have always played a significant role in my life. I spoke Pig Latin until someone revealed it wasn’t actually spoken anywhere, and then I was exposed to Spanish in fourth grade by an inspirational teacher. And my love of and exposure to other languages (Portuguese, French, Italian, German, and Russian) allowed me to leave an unhealthy situation in Missouri and move to Maryland in 1985 for a job with the government. It was in this job that my work with African languages began: the click languages of Xhosa and Sotho, followed by Shona, Swahili, Amharic, and a smattering of Somali.

As I wrote in Immersion, languages were a window through which I saw myself more clearly. As I studied these other languages, I was able to plumb the depths of each language’s secrets, searching for hidden meaning and culture inside the idiosyncrasies of these languages. And I began to examine myself and my life through the filter of these non-English languages. And I actually learned more about myself, I think, which was crucial when I began writing my essays and memoirs.

You’ve published two memoirs. Can you talk about the beginnings of your first memoir, Ivy Lodge? Did you begin with essays or maybe even short fiction, or did you start with the book itself?

Ivy Lodge began life as a ten-page essay I wrote at the Iowa Summer Writing Festival in 2014. The assignment was “Writing About Nowhere,” and students were tasked with digging into the details of something in our lives, and expanding on those details. I chose my childhood home, Ivy Lodge, and in writing about that place, I uncovered many things about myself, my family, my life, things I amazingly had never considered before, even though I was in my fifties when I wrote that essay. When I returned home I felt compelled to continue that journey with my childhood home, and began writing Ivy Lodge: A Memoir of Translation and Discovery.

What do you know now as a writer that you wish you’d known starting out?

Writing is enormously rewarding and, as my second act, it has taught me many things about myself and about the writing world. But I wish I’d known the amount of rejection that’s involved. Maybe non-writers assume that it’s all smooth sailing with submitting our work but, at least for me, that has not been the case. About two dozen of my essays and stories have been selected for publication, but many more than that have been rejected, and the lesson I’ve learned, but didn’t know at first, is that you can’t take it personally. Maybe it wasn’t the right fit for the literary magazine, or maybe they chose a similar piece last month, or maybe it was a little long, or a little short, for their needs. You’ll usually never learn the reason, but I’ve learned that you just have to keep writing and honing your craft and submitting and not let one (or ten or fifty) rejections defeat you.

Can you share a challenge you’ve faced with writing, publishing, or both?

As an introvert—believe it or not!—I’ve found it challenging to be involved in all the pre- and post- publication marketing and publicity for my books, which of course involves book signings, interviews, book readings, book festivals, reviews, etc. I’m enormously grateful for any and all attention Ivy Lodge and Immersion have received, and wouldn’t change any of it, but it does go against the grain of my natural tendency to be more of a hermit.

In short, unless you’re a well-established author with a 24/7 publicity team, most authors I know have had to learn to be more assertive in promoting their books and, at least for me, a female raised in the Midwest in the ‘60s, that goes against the grain of what I was taught that “ladies” do: talk about themselves and their work.

I would also add that, sometimes, people with seemingly good intentions will ask me questions which I suspect they wouldn’t ask a male author: “What do your family members think of your memoirs, have they read them?” “Do they disagree with what you’ve written?” In my opinion, the books are self-contained entities that now exist outside of me, the author, so I prefer not to answer questions that really aren’t germane to the content of either memoir, if that makes sense.

What makes a midlife writer a stronger writer?

I think I’m more flexible as a midlife writer than I was when I was in my twenties or thirties. I’ve experienced setbacks, personal tragedies, and many challenges, so that has been my training ground, along with having experienced much joy and recognition. When you’re a midlife writer, I think you have a better idea of who you are and what you want and you also realize you don’t have decades at your disposal to futz around and figure things out. You need to move ahead now, because you realize how short life is, and you know not to worry about what other people are saying or doing; you follow your own path.

Can you share your advice for someone who’s just getting started with writing, or who thinks it’s too late?

For me, the lesson for other writers, regardless of the trajectory in their career, is twofold: first, not to compare yourself to younger writers who have years ahead of them in their writing lives. What’s the point? And second, to cultivate a strong habit of persistence. As Calvin Coolidge said in my favorite quote (paraphrasing): talent, genius, and education don’t count for much in the long run; it’s persistence above all. So, when your essay or manuscript or poem gets rejected, or someone leaves a harsh review of something you’ve written, etc. don’t let it stop you. Keep writing. There’s no time to dwell on it.

One more thing, when I was working on my MFA, I felt self-conscious that I was the second-oldest person in my class, and a friend remarked that the days and years pass regardless, why not spend my time doing what I want to do, what I love to do, and not worry about how “late” I was to the game.

Say a little more about going back for your MFA degree.

About ten years ago, a good friend told me about the low-residency MFA program in which she was enrolled, and this model sounded perfect for my needs: meeting in-person twice a year for a week-plus, and then sending in packets to a writer/advisor between those in-person sessions, with reading assignments and communication with that advisor during the remote period.

I applied to five low-residency programs, and part of the application consisted of submitting quite a bit of my writing. I picked VCFA based on the faculty, many of them well-known writers, and its reputation for educating its students not just about writing, but also about practical aspects: craft, publication options, etc. A bonus was making friends with fellow writers—some in my cohort, but not all—friends I still keep in touch with.

Do you think you got more out studying creative writing at a later age, or just something different than you might have at a younger age?

I do think I got more out of the program at an older age than I would have when I was younger. I had just retired from my work as a multi-linguist for the government and was ready to go full steam ahead with my writing, and my kids were on their own and self-sufficient, so my mindset was perfect. And the program felt like the combination of a formal master’s program, coupled with a vocational/practical bent, where I would, and did, learn the tools of the trade.

I know there are many many successful writers who don’t have an MFA, but for me, it was just what I needed to jump-start my writing, to get it to the next level. I learned so much, I can’t imagine having achieved whatever success I’ve achieved now, without that MFA.

I had to leave my home country and my language of origin to find myself, to discover that I had worth, that I was not the (inferior) person I’d been led to believe I was. Leaving home and leaving English behind temporarily were the keys to that metamorphosis, to helping me believe in myself, in my worth.

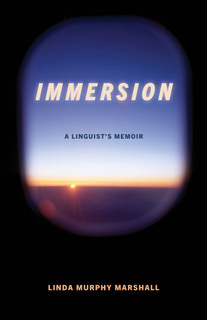

Tell us about your most recent memoir, Immersion, and if you’re working on another project now, talk a little about that.

Immersion is both a continuation of Ivy Lodge, and a stand-alone memoir. It’s primarily about my top-secret work for the government as a multi-linguist, and the adventures I went on, primarily in countries in Africa. The book also includes a chapter about a watershed trip to Brazil’s favelas and its outback, a trip that emboldened me to leave a toxic situation, and move to Maryland with my two tiny children.

The bulk of Immersion deals with the physical and emotional challenges of being sent to countries in Africa as a multi-linguist. It highlights some of the most memorable assignments: to Zambia, where a coup broke out the day I arrived, to the Democratic Republic of Congo in the middle of a war, to Kenya shortly after al-Qaeda bombed the US Embassy, to Tanzania as a Swahili linguist with a team assigned to protect President Bush, to South Africa shortly after apartheid was abolished, to Ethiopia, and elsewhere.

I had to leave my home country and my language of origin to find myself, to discover that I had worth, that I was not the (inferior) person I’d been led to believe I was. Leaving home and leaving English behind temporarily were the keys to that metamorphosis, to helping me believe in myself, in my worth.

One of the main reasons I wrote Immersion was that I wanted to leave a record of some of my life-changing and often-terrifying assignments. People working for the government are discouraged from talking/writing about their work, but it felt important that I leave behind a legacy of who I was, what I had done, and who I had become. I knew that I’d been part of some historic assignments, always interesting and often dangerous, and I wanted to to tell my story.

I had to get special permission to submit my manuscript to publishers, and the State Department, the CIA, NSA, and the FBI all had to sign off on my memoir. But it was worth the wait to be able to tell my story.

As far as new projects go, I’ve been writing essays for nearly ten years, and more than two dozen have been published so far, so I’d like to continue working on my essays, and perhaps compile them into a book. But I’m only at the beginning of that process.

And if you like, tell us about a book/books that you think deserve more attention.

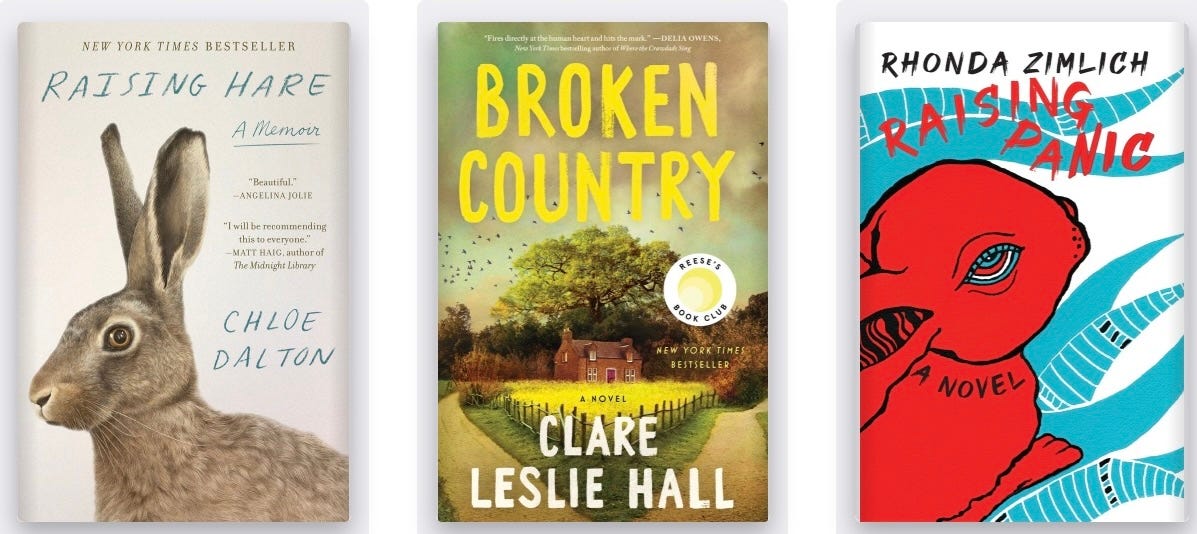

I really enjoyed Raising Hare: A Memoir, by Chloe Dalton (2025); it’s different than any memoir I’ve read recently. Raising Hare is about a British woman living at her country place during the pandemic, and her life is changed when a hare (not a rabbit—not the same, I learned!) crosses her path, and becomes part of her life. It’s beautifully written and so different. I also loved Jennifer Friedman Lang’s Places We Left Behind (2023), with its insight into the challenges of navigating an international marriage.

And I just finished a beautiful novel: Broken Country by Clare Leslie Hall. I hadn’t really wanted to read it, but did at the urging of a friend and loved it. And last, I couldn’t put down Rhonda Zimlich’s brilliant new short novel Raising Panic. I’ve also read quite a few of her stories and essays, and her amazing work deserves much more attention.

Book giveaway details

For Women’s Fiction Day (yes, that’s a thing, and it’s June 8; we can discuss the troublesome phrase Women’s Fiction another time), my novel The Wrong Kind of Woman is part of a giveaway—one reader will receive these seven signed books. To enter the giveaway contest, click the photo below, or use this link.

Until next time! Let me know what you’re reading this month. 📚

I’ll leave you with two views from here: the double rainbow over our field last week, and Otto “swimming” in the pond down the road.

Great interview and now I have more books to add to my TBR list.

I'm almost finished reading Nickolas Butler's A FORTY YEAR KISS. Premise is two people who were briefly married in the late 70s/early 8s meet up again in a bar and an unfinished story picks up to see if they can write a better ending.

Thank you for this fabulous interview. Always so interesting to see the perspective of other writers. Always so reassuring.