Like a character out of a Wharton novel: Isabella Stewart Gardner

Hi friends! Today I’d like to tell you about the first woman to found, build, and fill her own art museum, Isabella Stewart Gardner. Belle, as her family called her, could almost have been a character in an Edith Wharton novel. Born into wealth and privilege in New York City, Belle married the brother of her best friend from her Parisian finishing school. This was Jack Gardner, and he was very much a Boston Brahmin—Jack’s middle name was Lowell; his brother’s was Peabody.

But once the couple settled in Boston, the city’s Brahmin/society women snubbed her, leaving her out of their sewing circles and other gatherings, and gossiping about her. Too New Yorky, too exuberant, doesn’t know her place, too show-offy with that tiny waist, all the the jewelry and Worth dresses, they might have said about her.

Soon, things got worse: Belle suffered a stillbirth, then tried for years for another pregnancy. At last, she delivered a healthy baby bow, nicknamed Jackie. But at only two years old, Jackie, who’d had a bad cough, grew sicker, and died. Then the losses piled up: A niece and a nephew died of cholera, abroad; Belle’s siblings died; and sister-in-law Harriet died after childbirth. And Belle herself, who’d been doing poorly, suffered another late miscarriage. The family doctor prescribed a trip to Europe as a cure; she was carried on a stretcher to board the ship.

Grief sent the Gardners traveling, but this is not a Whartonesque tragedy.

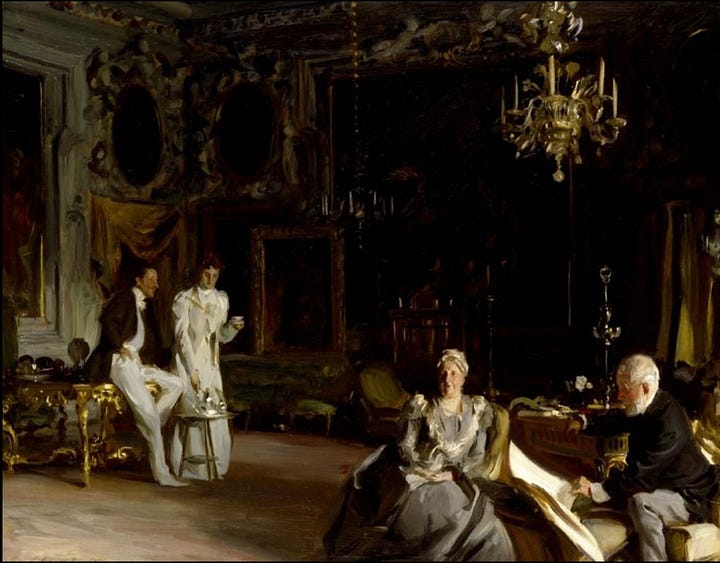

Belle began a self-study of art and artists, music, and literature—she was an early member of, and one of few women in, the Dante Society, a group of academic luminaries who gathered for lectures on Dante’s works. She attended art lectures, filling notebooks with details about artists and their works. After that first trip abroad, she and Jack criss-crossed Europe, the Far East, the Middle East, with long stints of travel most years, and long stays in London and Paris, and in Venice, at the Palazzo Barbaro, owned by a Boston couple, the Curtises, who had fled legal trouble in Boston and now lived mostly abroad.

Her friendship with Sargent and James

Soon Belle, or Mrs. Jack, as her friends and family later called her, was building friendships with artists, writers, and musicians, most notably Henry James, who was about her age, and John Singer Sargent, 16 years younger. She remained lifelong friends with both men, especially Sargent. All three shared an affection for Venice—Sargent painted watercolors of Venice throughout his life (Sargent was also a cousin of the Curtises, and good friends with their artist son Ralph Curtis).

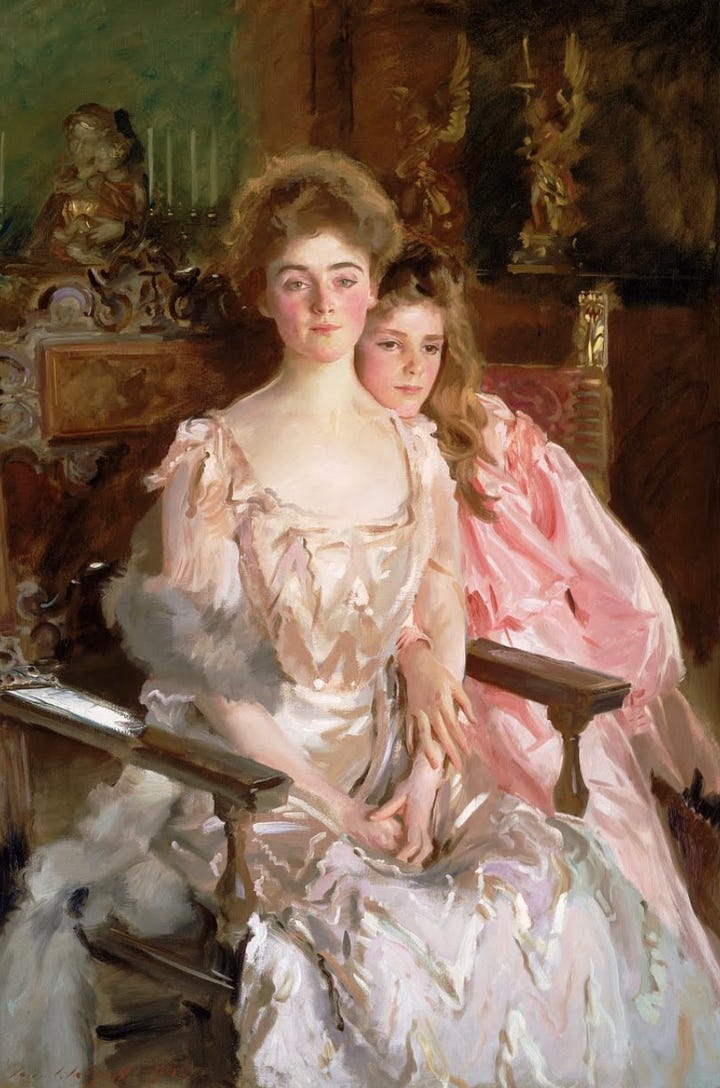

Introduced by Henry James, Belle first met Sargent at his London studio, and she was struck by Sargent’s Madame X portrait, the picture that had driven him out of Paris. Soon after that, she commissioned a portrait, which he painted during a long visit to New York and Boston. Because this was Boston, there was gossip that Belle and Sargent were having an affair.

Her life’s work began at midlife

Around this time, Belle began her life’s work of collecting pieces of art that she was passionate about. Some of them were Old Masters—she brought the first Raphael and one of the first Vermeers to America, and the first Titian to Boston—but also non-Western art, early manuscripts, and contemporary paintings. American Gilded-Age plunder? Well, yes, it was; and her collecting helped set off a cascade of intense art collecting among America’s wealthy.

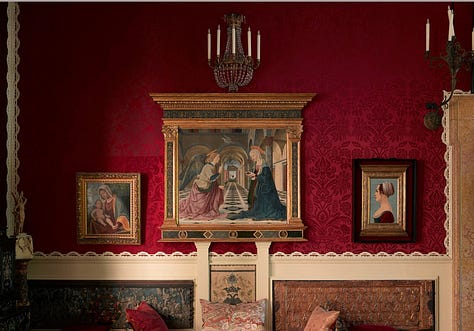

After Jack died, in 1898, Belle began her biggest project: a house-museum to hold all her treasures, supervising the design and building. From the outside, the house looked like a large, rather plain, four-story mansion set in the marshy Fens of Boston, but its inner walls evoked a Venetian palazzo and surrounded a large glass-roofed courtyard. She called it Fenway Court, and she lived there part of the year through her later years, opening the museum to the public a few days a year.

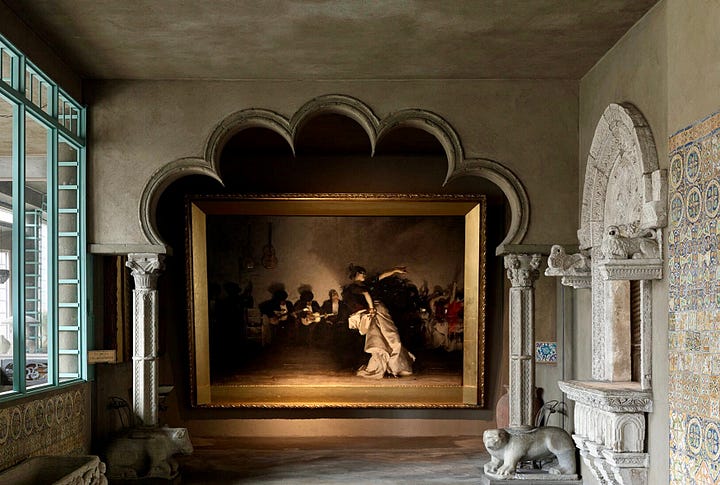

Sargent was Fenway Court’s first artist in residence, and he sketched and painted portraits there; Belle devoted an entire room to Sargent’s large-scale early picture El Jaleo, which she’d bought years before, and he hated walking past it each morning. (See below.)

In the end, Mrs. Jack was Sargent’s best patron, buying 60 of his pictures.

Mid-century curator Katharine Kuh, born in 1904, shared in her memoir a memory of Sargent and Gardner from her own youth. Kuh had had polio as a child, and her mother regularly took her to Boston for doctor appointments (probably around 1916-1918, when Sargent made several long stays in Boston).

“Sargent was handsome and elegant, Mrs. Gardner severely bent and dressed in what always looked to me like layers of cheesecloth…Since I have become equally old and bent, I understand her costume better. She just wanted something soft and unrevealing to hide behind. Their conversation appeared more sporadic than spirited, but there was a quiet forbearance between them signified a long friendship.”

During the trips to Boston, they stayed at the Copley Plaza and visited Fenway Court; Kuh’s mother also learned “that on precisely the same day of every week at precisely the same time John Singer Sargent joined Isabella Gardner for lunch, and they say at the exact same table.” Kuh’s mother tipped the maitre d’ for a table nearby.

“Sargent was handsome and elegant, Mrs. Gardner severely bent and dressed in what always looked to me like layers of cheesecloth,” Kuh writes. “Since I have become equally old and bent, I understand her costume better. She just wanted something soft and unrevealing to hide behind. Their conversation appeared more sporadic than spirited, but there was a quiet forbearance between them signified a long friendship.”

If you visit the Gardner Museum today, you’ll see that it remains as Mrs. Gardner left it—she specified in her will that the museum was to be open to all, with an endowment to keep it going, but that all the items needed to stay where they were, with no accompanying labels. This is something that Boston art lovers know, that Mrs. Jack created an incredible but idiosyncratic collection, to forever remain arranged as she’d planned it.

It’s less well known that in her will, she also specified that after her death, the museum’s name would change, from Fenway Court to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. One last bold move, from a bold woman.

Further reading:

I researched Isabella Stewart Gardner back when I was writing my novel about Emily Sargent and John Singer Sargent, and I wanted to include more of her in the novel, but in the end she only appeared in brief references. Here are a couple of recent books about Mrs. Gardner, plus one more.

—Chasing Beauty, Natalie Dykstra. Dykstra’s biography of Mrs. Gardner, published this spring, is fantastic—well researched, complete, but very readable.

—The Lioness of Boston, Emily Franklin. I haven’t yet read this historical novel, which published last year, but it’s gotten a lot of love in New England

—My Love Affair with Modern Art: Behind the Scenes with a Legendary Curator, Katharine Kuh, republished in 2012. Kuh was the mid-century curator who told the story about seeing Mrs. Gardner and Sargent eating lunch at the Copley Plaza. This book is more about 20th-century art and artists.

We’ve been traveling in Italy this week, and I’ve been thinking about novels about travelers to Italy, like EM Forster’s A Room with a View, Elizabeth von Arnim’s The Enchanted April, and Sarah Winman’s more recent Still Life. More on Still Life, below.

The novel I avoided reading for two years

I must confess that Sarah Winman’s latest novel Still Life (2021) was a book that I avoided when it came out; there was something about the book’s cover that didn’t appeal, or maybe just confused me (a novel about a parrot? No thanks). So I’m not sure what made me pick up

Until next time! I’ll leave you with a couple of views from here—the dramatic sky over our old barn the other night, which reminded me of a Maxfield Parrish or NC Wyeth painting, and a summer bouquet with the last of the New Dawn roses.

Glad you mentioned Natalie Dykstra’s Chasing Beauty. It is excellent! Anyone interested in Gardner should read it. ❤️

Lovely tribute piece. I remember visiting this museum as a kid and the great art theft. And I can relate about the research on her and then only using a passing reference in your novel. It's often the case but what an amazing rabbit hole you followed.