On late bloomers, flowers, friendship, and Mary Delany

Or: Beginning your life's work at age 72

“A life’s work is always unfinished and requires creativity till the day a person dies.” — Molly Peacock

Today I want to tell you about a different kind of late bloomer.

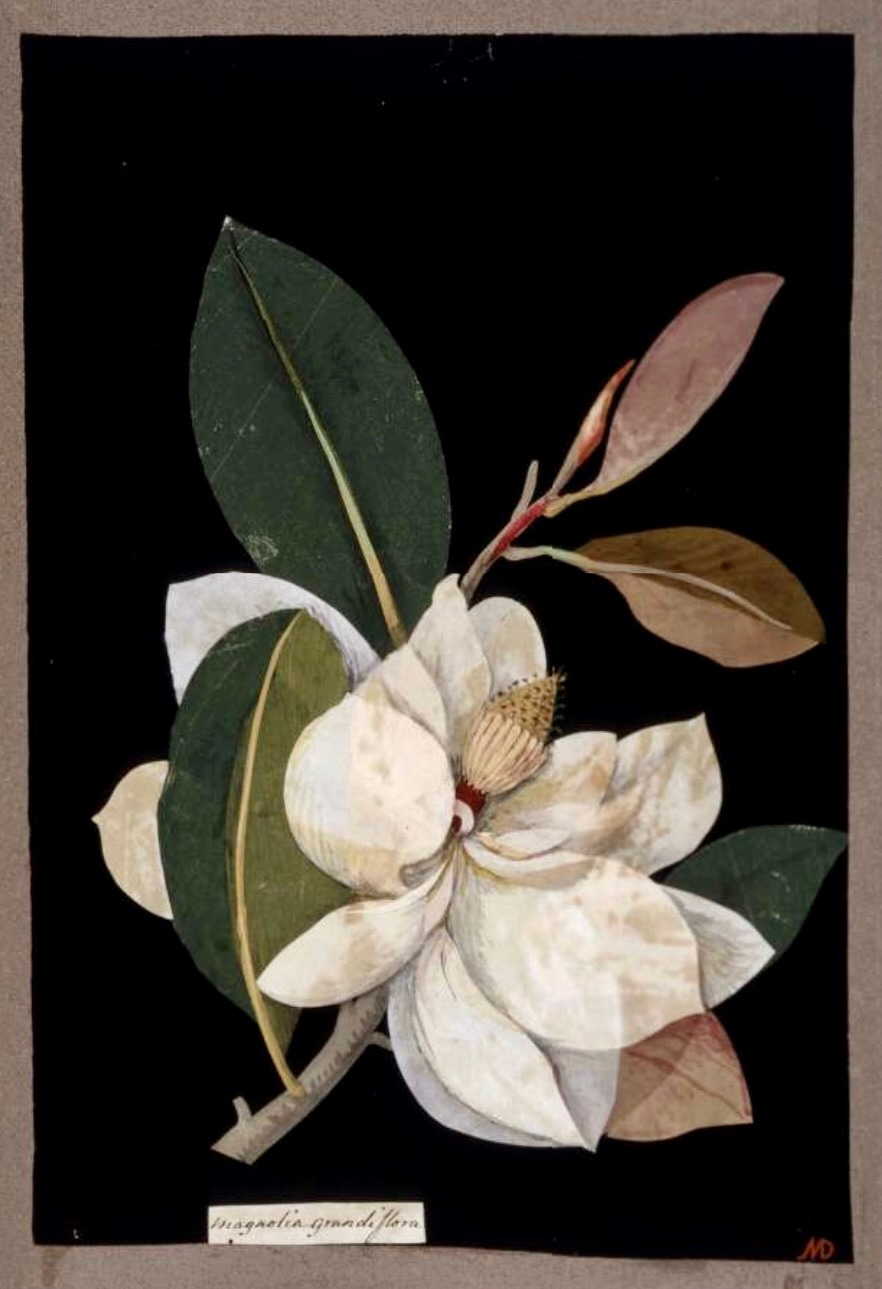

She lived 300 years ago, an Englishwoman whose life held echoes of Jane Austen and George Eliot. Her name was Mary Granville Pendarves Delany, and at the age of 72, she more or less invented collage, combining her interests in art and science to create something new. She made astounding, botanically correct renderings of flowers, using tiny scraps of paper, scissors, and paste—almost a thousand in all, until she was 83 and her eyesight began to fail.

But decades before that, marriage was the main preoccupation for Mary’s family; she’d been brought up to expect a position at court, with the usual skills in painting, drawing, needlepoint, horsemanship, fluent French, and music (she played for Handel, and they were mutual admirers). Her family married her off at 17 to Alexander Pendarves, an abusive, alcoholic, 60-year-old with a fortune. Pendarves died after seven years of marriage (thankfully). Though Pendarves didn’t leave her his fortune, widowhood left Mary relatively free to move around England, and she spent extended periods with her sister Anne, and her two close friends, Ann Donellan, and Margaret, Duchess of Portland.

Over the next 20 years, Mary turned down marriage proposals, went to court repeatedly to try for a lady-in-waiting position, and kept up her friendships with women and men, including the Irish author Jonathan Swift.

Tell me if this doesn’t sound like Jane Austen:

Why must women be driven to the necessity of marrying? a state that should always be a matter of choice! and if a young woman has not fortune sufficient to maintain her in the station she has been bred to, what can she do, but marry? and to avoid living either very obscurely or running into debt, she accepts of a match with no other view than that of interest. Has not this made matrimony an irksome prison to many, and prevented its being that happy union of hearts where mutual choice and mutual obligation make it the most perfect state of friendship?

Mary Delany asked these questions in a letter to her sister, in 1751. By then she had married again, to a man her family didn’t approve of, Samuel Delany. He was Irish, a Protestant cleric with no family pedigree, and in his 60s. He was also a longtime friend of Mary’s, through Jonathan Swift, and recently widowed. After a number of heartfelt letters and a meeting with Mary’s disapproving brother, Delany persuaded Mary to marry him, and they had 15 happy years of marriage, and of planning and adding to their gardens, collecting plants, and traveling between Ireland and London, until his death in 1768. (The gardens at their home, Delville, outside Dublin, became the beginnings of the National Botanical Gardens of Ireland.)

The year after Delany’s death, Mary began to translate William Hudson’s Flora Anglica (English Flora), a 400-plus-page compendium of English flowers, the first to use Linnaean terms, from the Latin.

A few years after that, she made her first collage, after she’d noticed how a piece of colored paper looked like a lone geranium petal. She called them her “paper mosaiks.” She colored the papers herself, including the black background paper that she often set the flowers against, and she worked from real life, sometimes from specimens that people sent her, as well as from renderings from early botanists who’d traveled to North and South America and Australia. Her close friend Margaret, Duchess of Portland, was a naturalist who collected the bound drawings these botanists made. Margaret also introduced Mary to some of those botanists.

Look closely at these collages: the petals, stamens, filaments—each is a tiny piece of cut paper, one layered over another.

Mary’s paper mosaiks caught the attention of Queen Charlotte, who began to send plants from the royal gardens at Kew, as did other plant collectors. Mary’s goal was to create her own Linnaean dictionary of flowers, Flora Delanica, a potentially endless project.

I learned about Mary Delany from my friend Meg, who’s a gardener, flower enthusiast, and an excellent correspondent. In a letter, Meg asked if I’d heard of Mary Delany, or of Molly Peacock’s biography The Paper Garden. The Paper Garden mixes memoir and biography—Peacock, a poet, weaves Mary Delany’s story together with pieces of her own story. It’s a wonderful book, well-researched and full of life, and I love the way she speculates about the unrecorded aspects of Mary Delany’s life.

Meg’s letter not only led me to Mary Delany, but it also got me thinking about the power of letters over time—there would be no biography of Mary Delany without the trove of letters she sent and received, all the thoughts and gossip and bits of philosophy and worries she exchanged with her sister, her husband, and her friends. Mary’s friends, like the Duchess of Portland, encouraged her to keep going with her Flora Delanica, her paper-mosaik project.

If you’re not familiar with biographer and poet Mary Peacock, here’s one of her poems, “Chance,” which resonates with me:

may favor obscure brainy aptitudes in you

and a love of the past so blind you would

venture, always securing permission,

into the back library stacks, without food

or water because you have a mission:

to find yourself, in the regulated light,

holding a volume in your hands as you

yourself might like to be held. Mostly your life

will be voices and images. Information. You

may go a long way alone, and travel much

to open a book to renew your touch.From The Second Blush, 2008, Molly Peacock.

And here’s Molly Peacock again, from the first chapter of The Paper Garden:

“Seventy-two years old. It gives a person hope.

Who doesn’t hold out the hope of starting a memorable project at a grand old age? A life’s work is always unfinished and requires creativity till the day a person dies.”

And last, here are some of the flowers from my garden this month, my own mix of art and science:

Further reading:

The Paper Garden, Molly Peacock, Bloomsbury, 2010.

British Museum, digital images of Mary Delany’s collages.

Letters from Mrs. Delany to Mrs. Frances Hamilton, 1779-1788, online (UCLA).

Mrs. Delany: A Life, Clarissa Campbell Orr, Yale, 2019 (I haven’t read this one)

I’m reading your lovely tribute to Mary Delany, as I’m watching two hummingbirds drinking from the native honeysuckle outside my window. I can imagine Mary creating a collage of the delicate honeysuckle flower. Once again, you have introduced me to an incredible woman and her beautiful artwork. Thank you!

Meant to say - your flowers are gorgeous!