"No one ever starts gardening either too late or too early, once it gets into one’s blood it can never get out (like some insidious poison)."

—Beatrix Farrand

Hi friends!

Recently my friend Meg sent me a card with an image of a pressed and dried clematis on it, and inside, a brief biography of the woman who preserved this clematis, more than a hundred years ago.

The woman was Beatrix Farrand, and she wasn’t only a woman who pressed flowers. She was one of our first landscape architects, and she, like Gertrude Jekyll in England, defined a look and style for early 20th-century perennial gardens.

Meg’s card felt like kismet, because I’d just been thinking about the stunning gardens at The Mount, Edith Wharton’s summer house in the Berkshires, which Farrand helped to design.

Beatrix Farrand could almost have been a character in a Wharton novel: like May Welland in Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, Beatrix grew up as one of “the 400,” the society insiders Wharton depicted, in a brick townhouse at 21 East 11th Street in New York City. She would have attended Assembly balls and similar social events, and she spent summers with her grandmother in Newport, RI, and her parents in Bar Harbor, ME. But Beatrix’ parents divorced when she was ten, and her mother Mary (Minnie) Cadwalader Jones, in need of money, soon turned herself into a literary agent, working out of the house on 11th Street.

As it happens, Beatrix was Edith Wharton’s niece, the only child of Edith’s oldest brother Frederic. Edith was only ten years older than Beatrix, and aunt and niece were close—Wharton took Beatrix along on European travels. Edith was also Minnie Jones’ first and best client as a literary agent.

Though a New Yorker, Beatrix was drawn to flowers and gardens from childhood. As she wrote about herself (in third person) near the end of her life:

“(Beatrix) became conscious of plants from her early childhood, as her grandmother took her into her rose garden at Newport, Rhode Island, and taught the child how to cut off dead flowers; and the four or five year old little girl trotted after her grandmother and learned many of the names of the lovely old roses of that day….As she grew up into girlhood, she naturally became more and more interested in plants, since she came of five generations of garden lovers.”

She also would have seen her mother Minnie and aunt Edith as women who worked and earned a living, at a time when women of their class just didn’t do that. (Minnie also hosted literary salons with writers like Henry James, who considered Minnie one of his best friends.) Beatrix, like her mother and aunt, grew up to be a prodigious worker and quiet barrier-breaker.

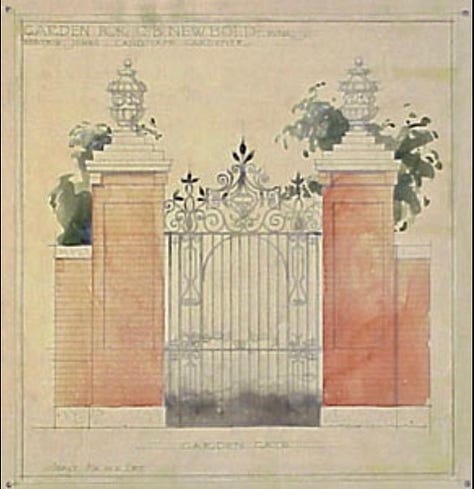

In her late teens, Beatrix met Mary Sargent, artist and wife of Charles Sargent, the head of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, and Mary Sargent invited Beatrix to visit them. Beatrix soon began studying landscape gardening, botany, and horticulture at Arnold Arboretum and at the Sargents’ estate in Brookline (there were no landscape architecture programs back then). Throughout her career, she would follow Sargent’s advice to work with the land’s features, fitting the plan to the site, rather than the other way around. Soon after, she studied with Frederick Law Olmsted’s firm, and traveled in England, Italy, France, and Germany to survey gardens, including those designed by Gertrude Jekyll. At 23, she started a business from a room in her mother’s house on 11th Street. And then she was off, designing gardens and hardscapes, at first for people in her circle, who had small city gardens, country estates, and money to spend.

At age 27, Beatrix was asked to be a charter member of the new American Society of Landscape Architects—the only woman included. She was confident enough to join the group, but also to call herself a landscape gardener, rather than landscape architect, in keeping with her love of gardens and gardening.

A few years later, philanthropist Margaretta Pyne connected Beatrix with Princeton University, and in 1912 Beatrix began designing gardens and hardscapes for Princeton’s campus, ultimately working with Princeton for two decades. Other campus designs followed, including Occidental College, Oberlin, University of Chicago, Temple University, and Yale, where she served as landscape architect for 23 years.

And so did more commissions for estate gardens, like Abby Rockefeller’s estate in Seal Harbor, ME; Dumbarton Oaks, Mildred and Robert Bliss’ 54 acres in Washington, DC (yes, 54 acres, right in Georgetown); and Dartington Hall, in Totnes, Devon, England. She also designed the East and West gardens at the White House during President Wilson’s tenure, and a rose garden at the New York Botanical Garden.

In all her work, she mixed formal designs with wilder, natural-looking gardens, favoring native plants and local materials. She was often involved in garden maintenance, sometimes for many years. And though most of her gardens are now lost to time, you can still see her work at Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden, Dartington Hall, and Dumbarton Oaks.

Her work must have absorbed all her attention—the business grew to include three offices—but at 44 Beatrix met Max Farrand, a history professor, at a dinner at Yale University. They married, but agreed to let each other carry on with their work. And even when Max was appointed the head of the Huntington Library in California, and Beatrix went with him, she kept up her business, traveling between the coasts, and managing her East Coast offices from California.

Some accounts of her life note that her commissions came through her social connections. I wonder if those accounts would mention this if she weren’t a woman; with Gilded Age architects Charles McKim and Stanford White, or landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted and his sons, we don’t consider their connections, but they all (like so many professionals, then and now) relied on social connections, too.

Circling back to Edith Wharton and the gardens at The Mount: I wonder if aunt influenced niece, or niece influenced aunt? The Whartons began building their house at the turn of the century, when Beatrix was a young landscape architect, and according to The Mount, Wharton was its garden designer, and Beatrix Farrand an additional landscape designer.

In all, Beatrix Farrand designed 200 gardens over a 50-year career, and turned her Maine summer home into a library and study garden for landscape architecture students. Prolific, like her aunt Edith, but not an Edith Wharton character, after all.

For more on Edith Wharton’s house The Mount, here’s my post from last year.

How fascinating! I love the Mount’s gardens and grounds. I love knowing more about its landscape designer.

Beautiful article Sarah. I love reading about self-determined successful women from history. Her designs are fabulous and The Mount looks like heaven on earth.