Gustave Caillebotte: the Unknown Impressionist

And a little mystery about the women in his life

Hi friends! I went to visit my son in Los Angeles last week, and we had a marvelous visit to the Getty Center, which was new to us both. The big exhibit at the Getty is Caillebotte: Painting Men, a show organized by the Getty, Musee d’Orsay, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

This exhibit got me thinking about how we construct narratives about artists over time; and how some late-19th-century artists, like Monet and Renoir, remain household names, while others, like Gustave Caillebotte or Berthe Morisot, are less known or nearly lost to us.

If Gustave Caillebotte’s name rings a bell, it’s probably for this monumental Parisian streetscape, Paris Street, Rainy Day (an enormous painting, seven by ten feet). It won acclaim at the 1877 Impressionists’ show, a show that Caillebotte also helped fund.

Gustave Caillebotte, like Berthe Morisot, is one of the lesser-known French Impressionists, though in his time, he was more known, and occasionally celebrated. The painting above, for instance, was the talk of the 1877 Impressionist show. And as with Morisot, much of Caillebotte’s work has remained out of view, hidden away in private collections. And like Morisot, Caillebotte came from a wealthy Paris family. He considered himself an amateur painter—unlike most of the other Impressionists, he wasn’t trying to make a living with his paintings.

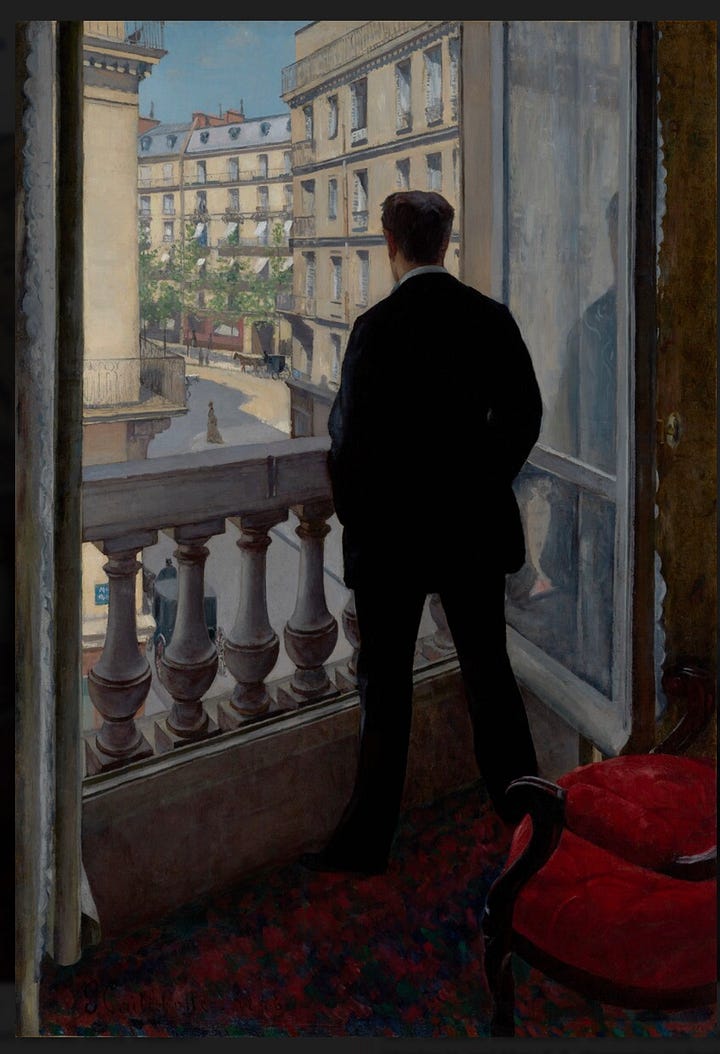

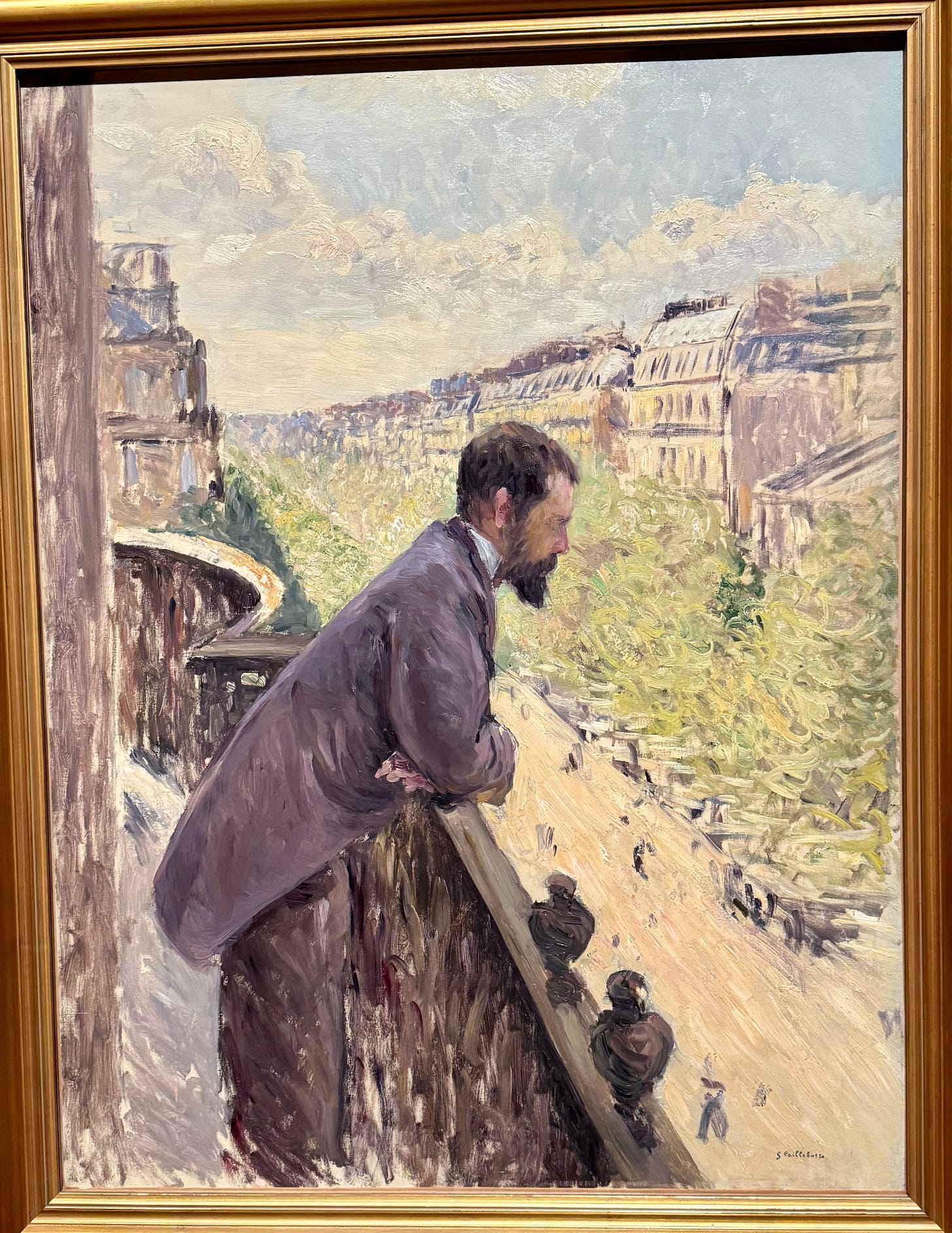

As the Getty exhibit’s title suggests, Caillebotte did indeed paint men, men walking through Paris, playing cards, toweling off, rowing, sailing, gazing out a Paris window. The exhibit’s name and its catalog descriptions hint at homoerotic desire, and Caillebotte never married. But to my eye, Caillebotte seemed to be painting playfulness or wit more often than he painted (or hinted at) desire.

In this playful reversal, below, Caillebotte puts a woman in the foreground, sitting up and reading the newspaper in a more serious, masculine way, and he places a man in the background, reclining on a couch—the spot where in other paintings a woman at leisure would be depicted, skirts flowing over the edge of the couch.

And here’s Caillebotte’s picture of his friend Richard Gallo, seated on a couch, a picture that made me laugh. Here’s a fancy brocade-covered couch, and a person on the couch, but it’s the opposite of an odalisque gazing at the viewer. Nor it is a bourgeois woman, reclining and reading a book. Instead, a man with his arms crossed stares into the distance, newspaper still in one hand—he’d rather get back to reading the paper than carry on with this portrait-sitting foolishness.

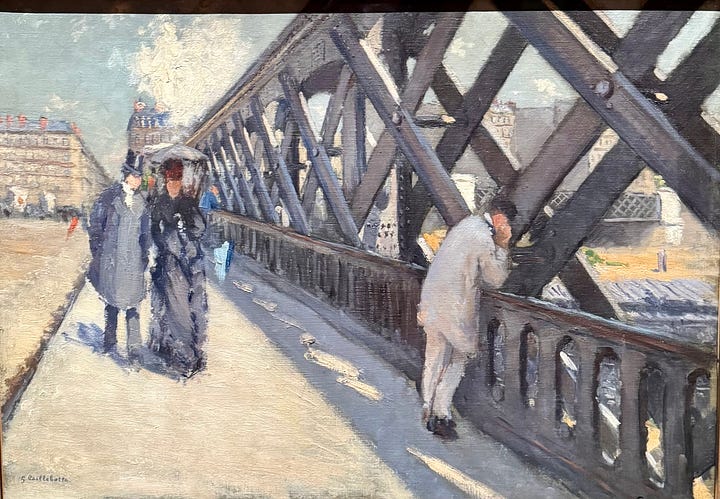

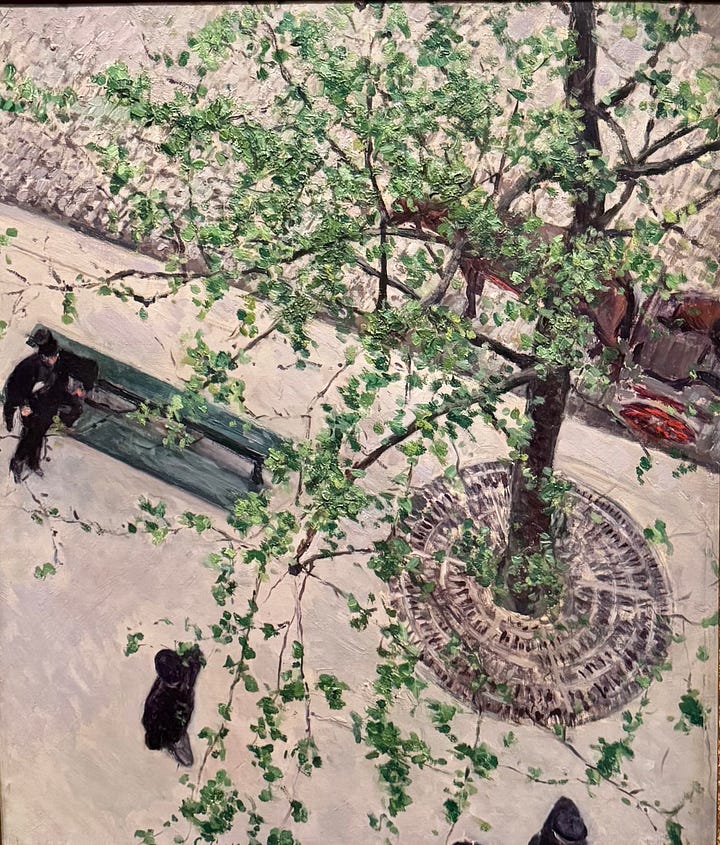

Caillebotte also painted urban landscapes from apartment windows, balconies, and his neighborhood, cropping the view and trying out odd angles, like these, below:

Here’s another urban view, Impressionist in its sketchy brushwork and hinted-at cityscape. The “Painting Men” exhibit text notes that Caillebotte liked to pose his friends in these balcony and apartment settings. Despite Richard Gallo’s apparent irritation with his sitting (above), he appears in several Caillebotte pictures.

“Caillebotte's art gives us only a partial glimpse into his life,” one of the Getty wall texts notes. But that hasn’t stopped art scholars from theorizing, based on the framework of the life and what’s they see on the canvas—Caillebotte was undoubtedly gay! Caillebotte was undoubtedly not gay!—much as they’ve done with John Singer Sargent.

And here’s a little mystery: Carillebotte never married, but after he settled in his country house Le Petit Gennevilliers, about ten miles outside Paris (not far from Monet’s Giverny), he lived with a woman named Ann-Marie Hagen, and then with another, Charlotte Berthier, for the last decade of his too-short life (he died of pulmonary edema at 45).

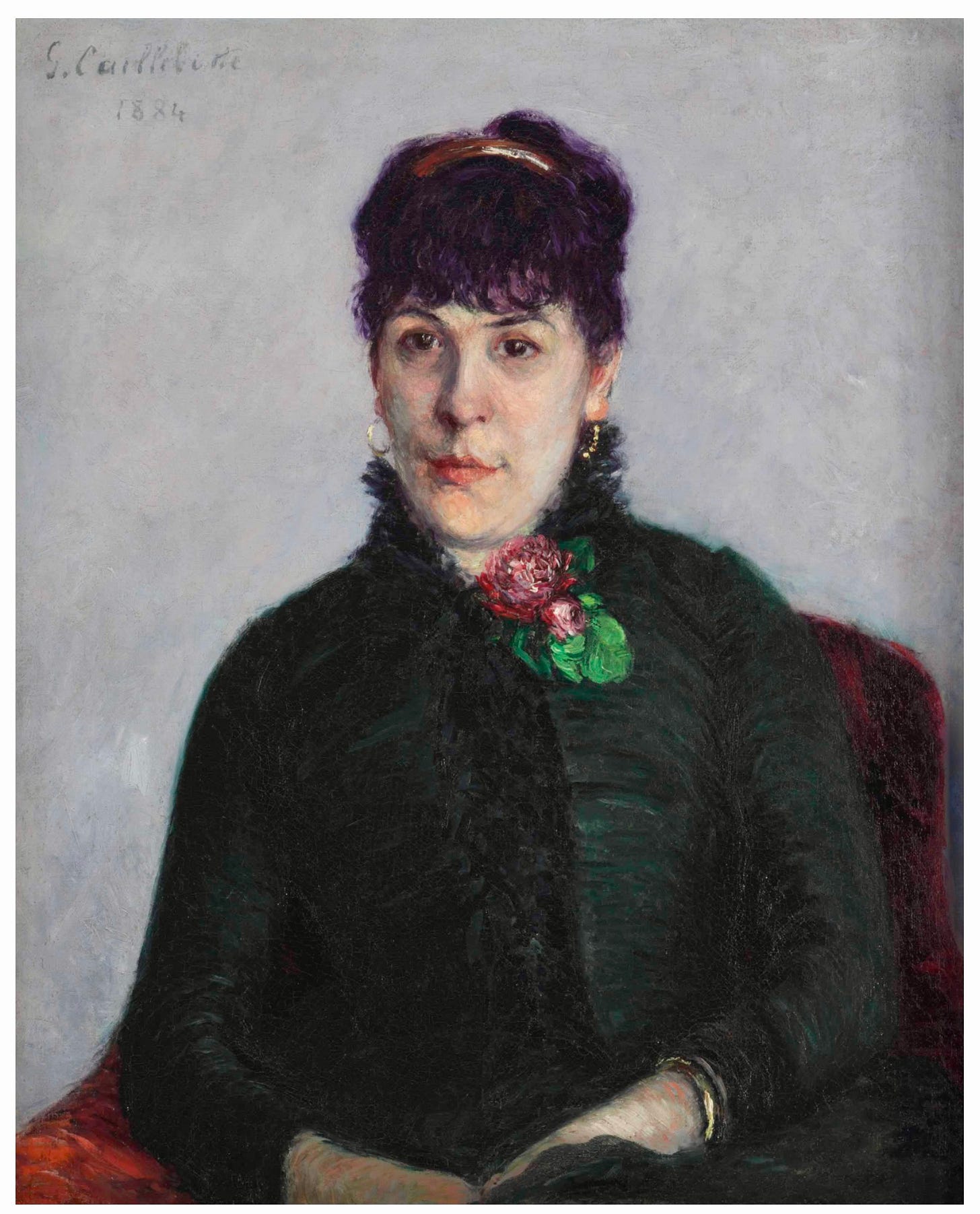

But some texts conflate these two women, saying that Charlotte Berthier was an alternate name for Ann-Marie Hagen. Caillebotte’s portrait below, “La Femme á la Rose,” from 1884, is of Ann-Marie Hagen.

An essay for Christie’s auction house notes that the relationship with Anne-Marie “was kept as quiet as possible, particularly from the artist's family. When she discovered the liaison, the artist's sister-in-law, Marie Caillebotte, refused to see the couple and forbade her husband to do so.”

“The cool reception of the family added to the painter's extreme modesty when it came to personal matters and may explain why Anne-Marie's imprint on Caillebotte's life and work remains obscure more than a century later. Nevertheless, she was a faithful companion for the painter for almost two decades, and lived with him until his untimely death in 1894, inheriting his house at Le Petit Gennevilliers in the event.”

The Getty/Painting Men catalog copy, on the other hand, calls Charlotte Berthier “Caillebotte’s longtime companion, noting that “they never married, and she rarely figures in his paintings, but she lived with him both in Paris and at Petit Gennevilliers, where a census listed her as Caillebotte's amie (friend). He also left her a significant annuity and a house in his will.”

Caillebotte mentions Charlotte in at least one letter to Monet, around 1884: “Charlotte [Berthier] has been in bed for a few days, so I have postponed my trip until next week. I hope she will get up in 2 or 3 days, and I intend to visit you in Etretat if you are still there next Wednesday by the morning train…”

And Caillebotte’s 1886 picture of the rose garden at his country house, below, features Charlotte Berthier and a little dog.

And here’s Renoir’s portrait of Charlotte Berthier, below, painted in 1883, when Renoir visited Caillebotte at Petit Gennevilliers. She looks nothing like Anne-Marie Hagen, the woman in “La Femme a la Rose” (scroll up to compare). The little black dog, though, looks a lot the one in the garden picture, above. Charlotte Berthier is apparently the nude in Caillebotte’s 1880 study Nude on a Couch, included in the Getty show.

It sounds like a novel waiting to be written, to fill in the gaps of what’s not known.

But here’s one aspect of Caillebotte’s life that is known: Over the years he bought many of his friends’ paintings, and his will bequeathed 70 Impressionist works to the French government. That group of paintings became the nucleus of the the wonderful Musee d’Orsay in Paris.

Gustave Caillebotte: A generous artist, friend, and Frenchman. And, probably, protector of his privacy.

For more Impressionism, here’s one of my posts about Berthe Morisot, below, a recent talk with the three curators of the Caillebotte show, and wall text from the 2015 National Gallery of Art show Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye.

Until next time/À bientôt!

What an intriguing story. I first saw his work featured by Art Every Day, but I really like the background information you’ve provided about his life and the two women he lived with. Thanks for writing this!

Sarah, as a longtime admirer of Caillebotte, who can usually spot his style from across a gallery, I love this post, full of new information and new images. His creative signature is strong diagonals, which aren’t present in the portrait of a woman. I never would have guessed this one was his. You probably know the fine Caillebottes at MFA Boston.