Berthe Morisot, Édouard Manet, and how they (might have) affected one another

Morisot, a groundbreaking artist that the 20th century forgot

Hi, friends. For today’s post, I’m focusing on not quite forgotten, but also not exactly well-remembered artist Berthe Morisot, who I too had almost forgotten about.

Recently I went to see a small show, Manet: A Model Family at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. The concept behind the show is the role of family members as muse, as they were for Édouard Manet; he painted his family members over and over. But I came away from the show thinking about another artist (and family member), Manet’s sister-in-law, Berthe Morisot, who married Manet’s brother Eugene.

Like Manet, Berthe Morisot grew up in a prosperous French family, and her parents encouraged her artistic efforts. Morisot and her sister Edma studied with Camille Corot, and in their youth the sisters declared that they’d never marry and have children, but would devote themselves only to their painting. (Though Edma let go of that plan quickly, marrying a Naval officer and friend of Manet.)

Berthe and Edma may have met Manet and younger brother Eugene through their teacher Corot, but they could also have met the Manet brothers at the Louvre when they were all copying Old Masters, Berthe and Edma with their mother as chaperone. Soon after that, Berthe and Edma began to attend the at-home nights that Manet’s mother threw, and met other artists.

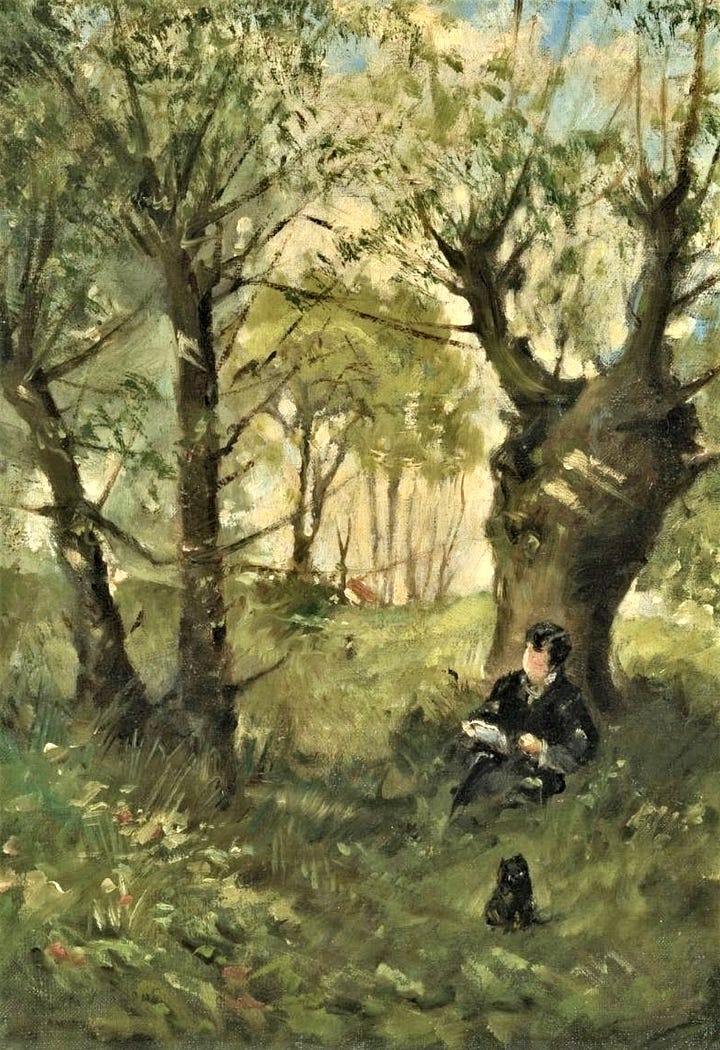

Morisot was a great admirer of Manet’s work, and he in turn was drawn to her—she posed for him repeatedly in her twenties and early thirties. The two must have talked about painting during those sessions. She was only 23 when she had her first picture accepted for the Paris Salon, in 1864 (around the same time that Manet’s Dejeuner sur L’Herbe was rejected), and she continued to have pictures accepted through her twenties, like these two landscapes below, with their loose and sketchy brushwork:

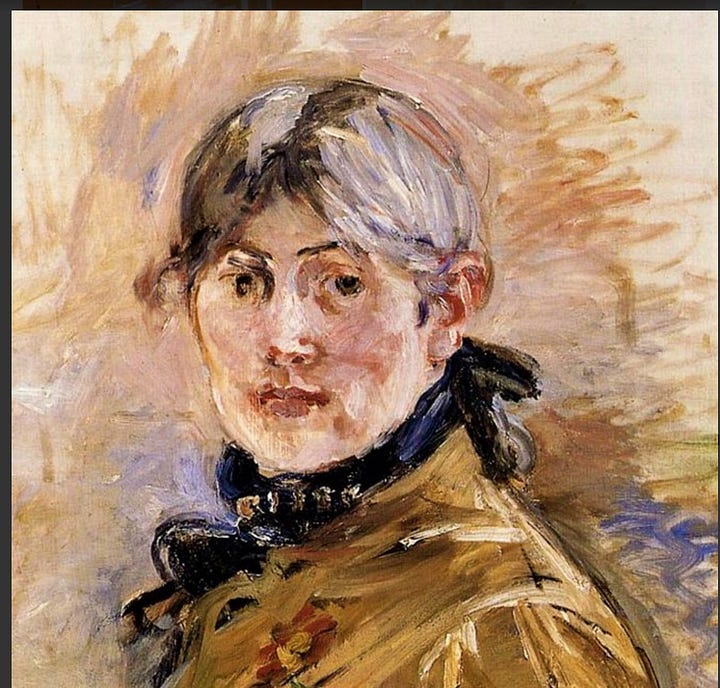

Morisot also painted portrait sketches of her family members, as Manet did. Here’s Morisot’s picture of her sister Edma, below on the left, and Manet’s portrait of Morisot, on the right. Both are from 1871. Morisot has taken on a more Manet-like style with this picture of Edma. With that straightforward gaze and flatness, there’s a hint of Manet’s Olympia and Dejeuner sur L’Herbe.

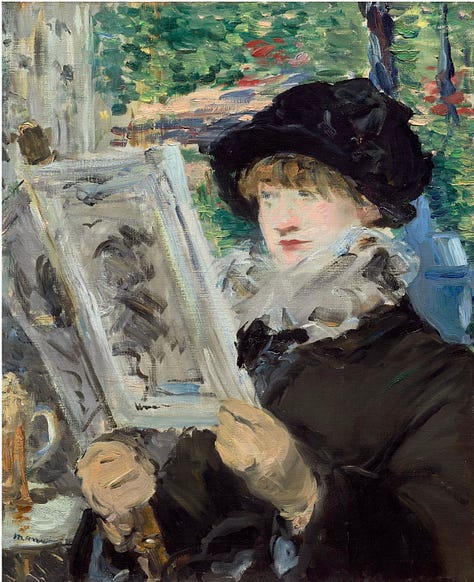

But Manet also painted portrait sketches in a more Morisot-esque style, like this one from around the same time (1869-1873). It’s another portrait of Morisot.

“The speed at which this portrait of her appears to have been painted, with its sketchy brushwork and unfinished appearance, echoes Morisot's own ambition and may have been Manet's nonverbal way to acknowledge her painting desires and to show her how he would achieve them.”

Artist Bill Scott notes that Morisot had a principle “never to try to rectify a blunder;” when things went wrong with a picture she abandoned it rather than reworking it. “Morisot observed that Manet once reworked a canvas 25 times to achieve an image that to him appeared effortless,” Scott writes. “She lamented how Manet "talked to me about finishing my work," and added, "I do not see what I can do." The speed at which this portrait of her appears to have been painted, with its sketchy brushwork and unfinished appearance, echoes Morisot's own ambition and may have been Manet's nonverbal way to acknowledge her painting desires and to show her how he would achieve them.”1

Meanwhile, at age 33, Morisot decided to marry Manet’s younger brother Eugene Manet, and Eugene, also an artist, pledged to support his wife in her painting. Morisot also stopped posing for older brother Edouard when she married Eugene. There’s been plenty of speculation about Morisot and Edouard’s relationship, and whether Morisot’s and Eugene’s daughter Julie was actually the daughter of Edouard. (Is there a novel about Manet and Morisot? I thought there was, but I haven’t been able to find it.)

But today, I’m mainly interested in how Morisot kept on painting, even after marriage and motherhood. She was one of the most stalwart of the Impressionists, exhibiting multiple pictures in all their shows, beginning with the first, in 1874. For the most part, art critics savaged that first Impressionist show, though a few praised Morisot’s The Cradle, below. This is a picture of Morisot’s sister Edma again, now a mother. Morisot captures not only that blue-gold light/shadow behind Edma (maybe a curtained window) and the translucent crib veil, but Edma herself, frazzled and weary and no longer painting.

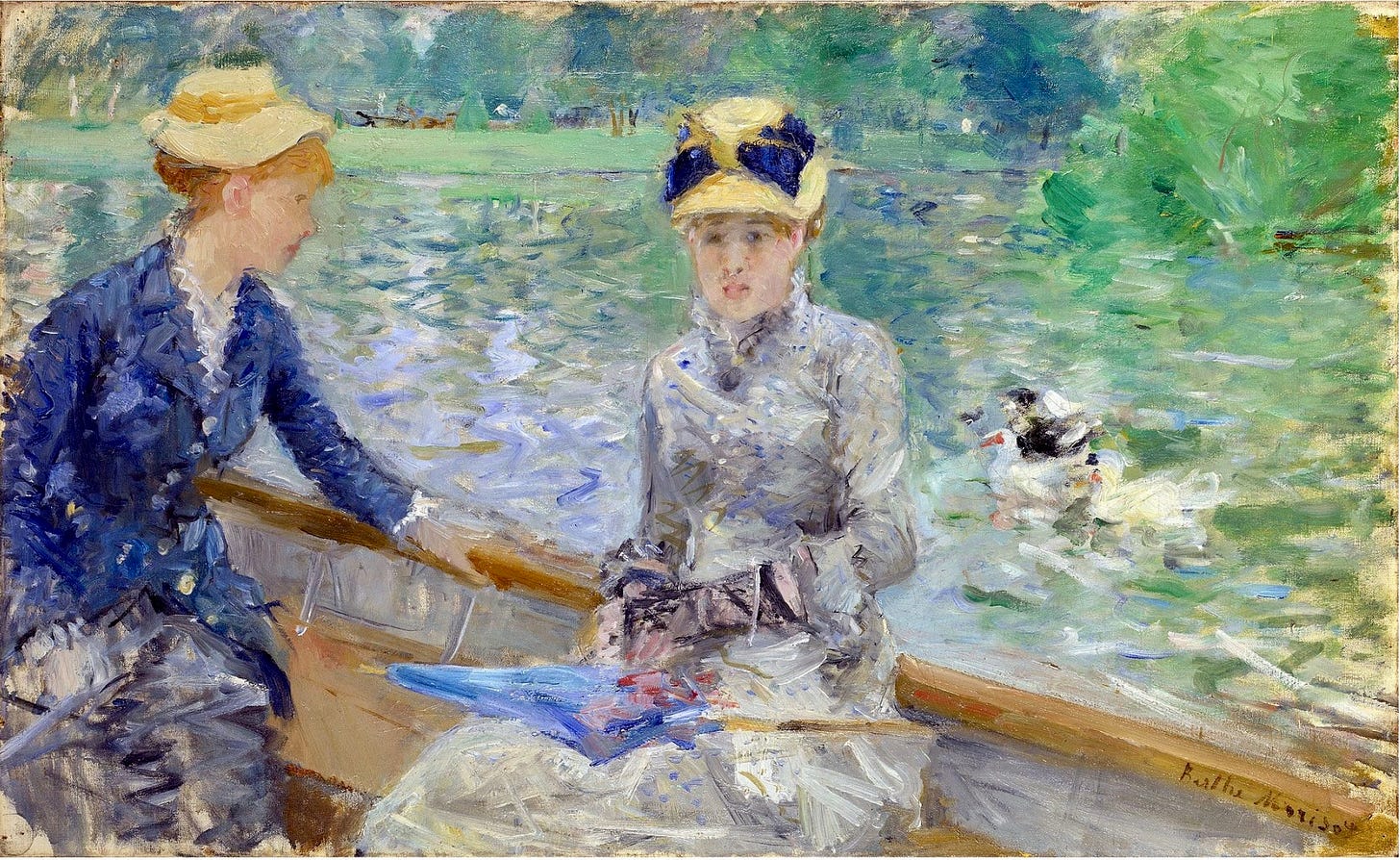

And look at the brushwork in Morisot’s outdoor picture, below. Look how immediate it feels, and how unfinished the dresses are; and the reflections on the pond are rapid thick swipes of paint. (Morisot and Mary Cassatt were friends, and I wonder if they talked about painting family members outdoors.)

Still, I have to wonder how Morisot’s work would have been received if she’d been a man. Would more of her works have gone into museums, rather than private collections? Would her name be more of a household word in the 21st century, like Manet, Monet, or Degas?

And two more, below, these two from the mid-1880s, a portrait sketch of one of Morisot’s favorite models, her daughter Julie (four years old here), and a self-portrait. Whatever those painting desires were that Morisot talked about with Manet years before, it seems that she achieved them.

Still, I have to wonder how Morisot’s work would have been received if she’d been a man. Would more of her works have gone into museums, rather than private collections? Would her name be more of a household word in the 21st century, like Manet, Monet, or Degas?

It turns out her work was well received, back then. It’s the 20th century that changed the narrative. Nicole Myers, who curated a 2019 exhibit on Berthe Morisot at the Dallas Museum of Art, said this about Morisot: “She was a founding member of the Impressionists, the only woman to join this rebel band of artists, and she was really well known and celebrated in her time. And yet in the 20th century, her role has been diminished, sometimes even eliminated, from the telling of the story of French Impressionism.”

Now I want to return for a minute to Manet. Look at these three pictures, which he painted in the early 1880s, close to the end of his life.

The brushwork is much looser than in his earlier paintings, the features and backgrounds sketchy. He’s taken on a more Impressionist style, which may have something to do with the pain he suffered from advanced syphilis (or possibly the treatment for syphilis), and needing to work more quickly on smaller subjects. But it’s also a more Morisot-like style, and I like to think that it grew at least partly out of ongoing conversations with Morisot. I like to think that her painting style affected his. (Manet died at 51, in 1883.)

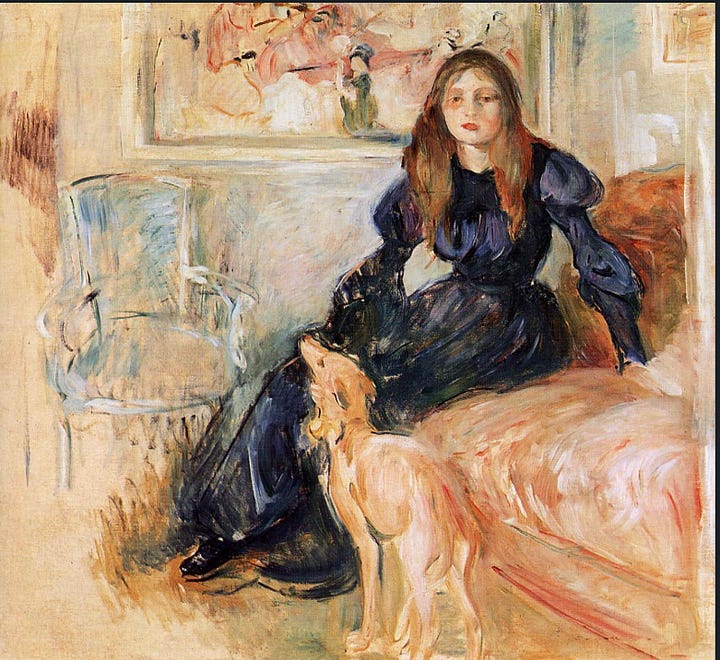

But that’s all speculation. What’s not speculation is that Morisot kept right on painting and exhibiting, after marriage, after motherhood, after Manet’s death, after Eugene’s death. Here are two more pictures that she painted of Julie: one with Eugene Manet in the summertime, and one from ten years later, of Julie grieving after Eugene’s death, in 1891.

As with her husband and her brother-in-law, Morisot’s life was far too short: After nursing Julie through pneumonia, Morisot got sick too, and she died at 54, in 1895. Julie was now an orphan at 16; she too would become an artist. (More on Julie in a post to come.)

For more on Berthe Morisot, here’s some background from the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. And here are two talks, this one with Dallas Museum curator Nicole Myers, and another with curator Helga Aurisch of the MFA Houston, about Morisot.

And for more on the woman who helped build the market for Impressionist works, and who built the beautiful, idiosyncratic museum to house her remarkable art collection, here’s my post on Isabella Stewart Gardner, below.

Excerpt from Bill Scott’s essay in the Manet: A Model Family catalogue.

Lovely, Sarah! This took plenty of focused attention, but you also must have enjoyed doing the study: such beautiful art. And we're learning that there are, alas, many examples of women artists, musicians, writers, scientists and more who weren't much recognized for their contributions. I know about Mary Cassatt mostly because an aunt of mine always loved her work; glad to know about Morisot now, too.

I enjoyed these telling juxtapositions of Morisot’s work and Manet’s. The novel, published by Freehand Press, is One Madder Woman by Dede Crane—beautifully written and deeply researched but not sufficiently compelling to keep me reading. Maybe I’m just quick to lose patience.