The midlife reinvention of John Singer Sargent and Emily Sargent

Plus your favorite reads of 2023

Last issue, I wrote about the artist John Singer Sargent, his sister Emily Sargent, and the years I spent (metaphorically) with them. This time, I’m sharing a little more about their lives.

*NB: If you’re reading this as an email, it may get cut off because of the photos. Click here to read.

Emily (b. 1857, Rome) and John (b. 1856, Florence) grew up all over Europe, staying in rented apartments and pensiones in Rome, Florence, Switzerland, Germany, packing up and moving every six months or so. Their mother, Mary Sargent, was restless: sometimes the family moved in order to meet up with another expat American or British family, sometimes because Mary was fretting about a cholera outbreak, bad weather, or Emily’s health. Mary and Fitzwilliam Sargent, who’d been a surgeon in Philadelphia, thought that Emily was so fragile she wouldn’t survive childhood.1 Emily had had an issue with her spine as a toddler (maybe spinal tuberculosis), and doctors advised the Sargents to keep her immobile for a year, when she was four. The treatment made her spine worse, leaving her with a misaligned spine, uneven shoulders and odd posture. All of this, and her parents’ worries, must have forced Emily into the background; and maybe she was more comfortable there, since she was self-conscious about the way she looked.

The Sargent children had essentially no schooling—their parents and occasional nurses taught them when they were little, and Mary Sargent taught her children to sketch whenever they were outdoors or sightseeing. As a preteen, John did a brief stint at a German gymnasium, cut short when Emily got deathly ill with a fever, and John also studied with painters in Florence and Rome. Despite their lack of formal education, John and Emily were both prodigiously well read and spoke French, Italian, and some German. And musical—John was so talented a pianist that he considered making a career of it.

On to the art

Painting-wise, John was such a prodigy that by the time he reached his late twenties, his pictures dominated at the Paris Salon competitions. (Though he was friends with some of the anti-Salon artists like Monet, John submitted pictures to the Salon as a young artist.)

Like his mother, John was restless, and in the summers he traveled with friends from Carolus Duran’s workshop, some of them American, though not all, or to stay with his family, who now pinged back and forth between Brittany or Normandy in summer, Nice in winter. For a couple of summers, John also took studio space in a decrepit palazzo in Venice, and the Sargent family joined him.

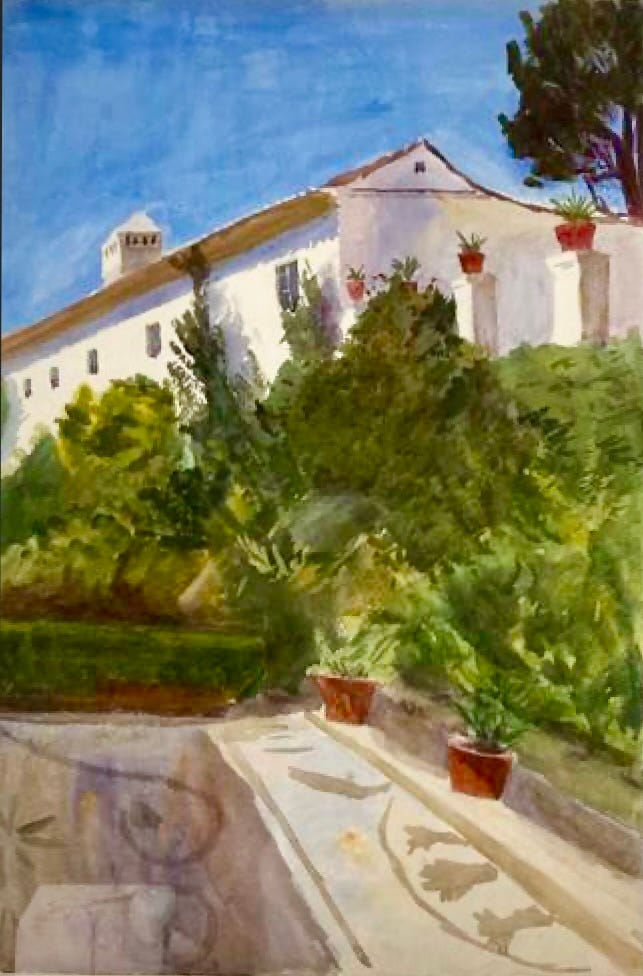

Here’s the kind of thing Emily sketched during those stays in Venice:

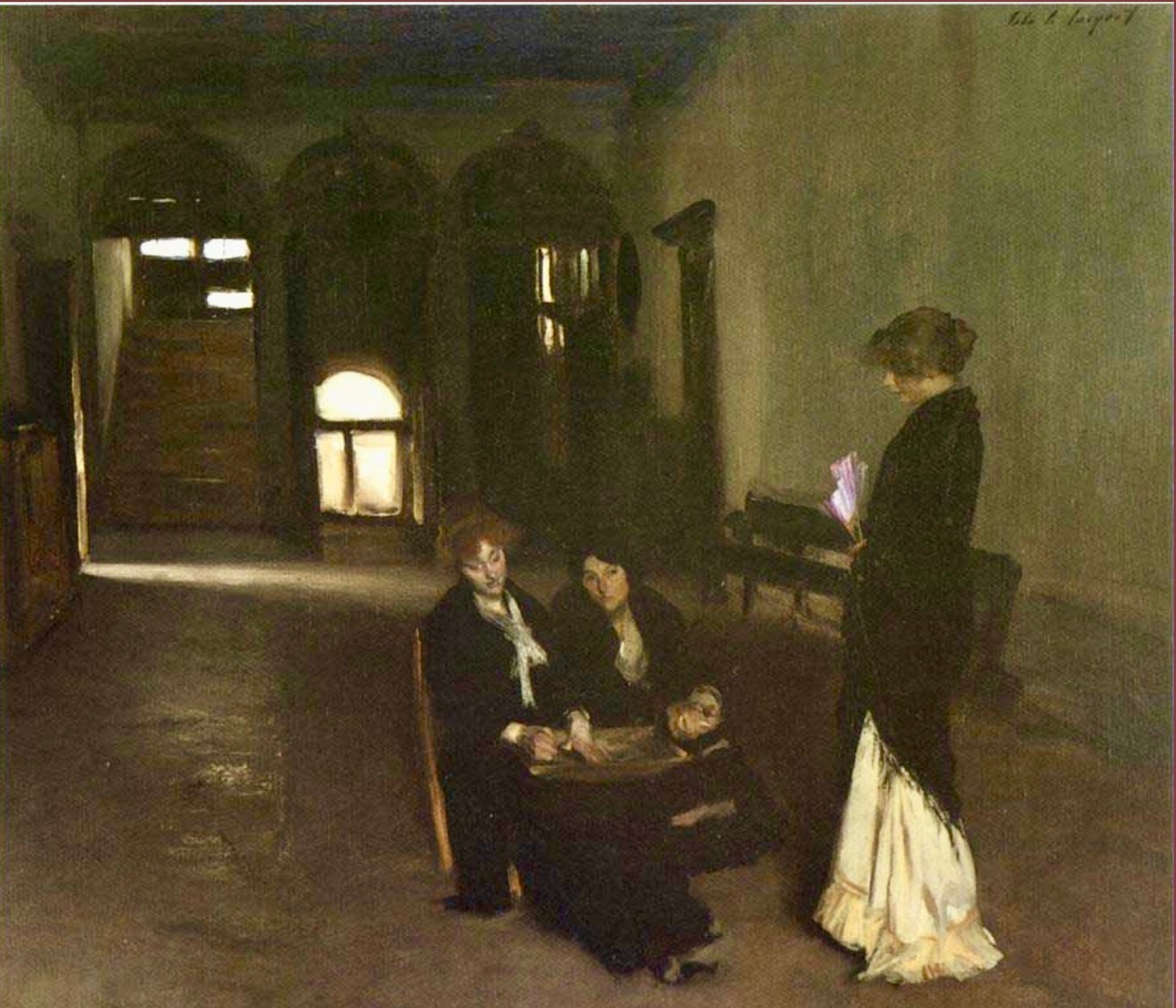

And John painted moody pictures like these two, below, and he had trouble selling them.

What John was able to sell were his unconventional portraits, like this group portrait of the daughters of American friends the Boits. He painted the Boit daughters at age 26(!). It’s almost a reworking of Velazquez’ Las Meninas, and it feels like a chapter in a Henry James novel. (Speaking of Henry James: he was struck by this painting, describing it as heartwarming or cozy, words that really don’t fit.)

And John was able to sell more traditional portraits, like the wife of the American ambassador to England, Mrs. Henry White, painted a year after the Boit girls’ portrait. So for the next thirty years, John made portraits, except for a year or so of uncertainty after his Madame X debacle, before he left Paris for London. By the late 1880s, John was ensconced in James Whistler’s old studio-house on Tite Street, Chelsea, in London. (Oscar Wilde lived down the street.) Emily and Mary Sargent soon followed, moving into a nearby apartment that John found for them.

Midlife and freedom

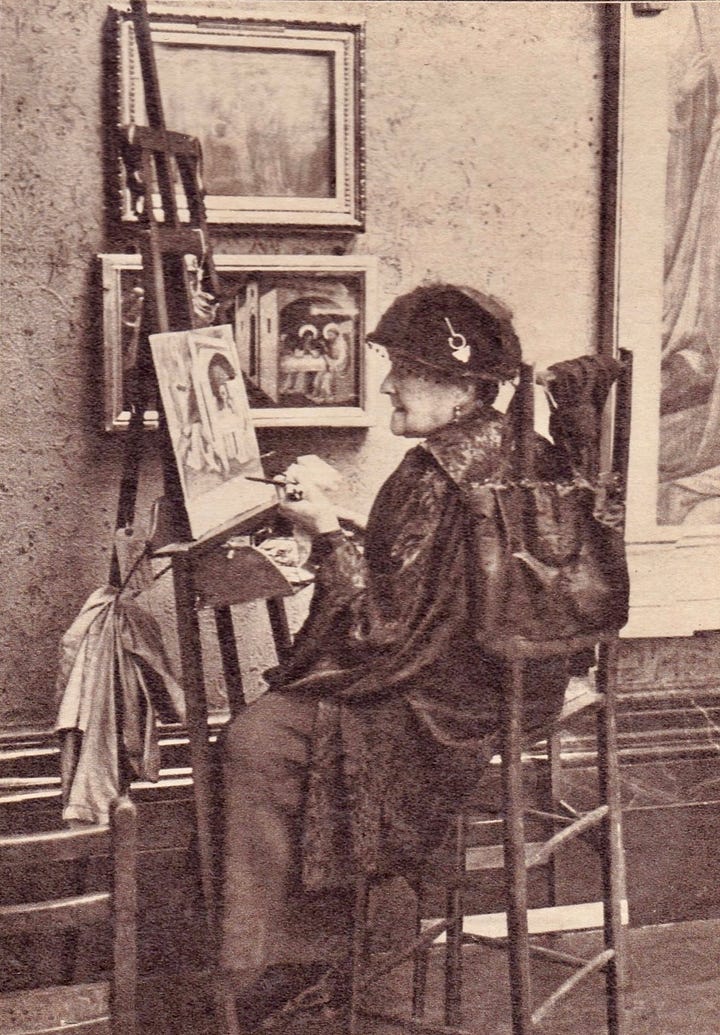

Midlife was a time of reinvention for both Emily and John. In 1906, when John turned 50, he declared that he was done with portraiture forever. (He gave in and periodically painted portraits over the next 20 years, and he drew hundreds of quick charcoal sketches of friends and paying strangers.) Around the same time, Mary Sargent died; Emily had been her mother’s companion and caregiver (Henry James described Mary Sargent as formidable, so I imagine she was a bossy mother). Mary’s death meant Emily was free to live her own life, painting more, studying with live models, traveling and painting with John and friends, occasionally showing her work in group shows like the New English Arts Club. And it turned out that Emily hadn’t succumbed to fragility; she lived on, traveling with John through Europe, the Middle East, and US, until her seventies.

“They knew each other’s unexpressed feelings; they communicated in a perfect but spare intuition; they used the same language without speaking; and they adored each other free of the need for reassurance…in time Sargent and his sister grew into one person.”

There’s a rather creepy quote about Emily and John in Stanley Olson’s 1986 biography John Singer Sargent: His Portrait: “They knew each other’s unexpressed feelings; they communicated in a perfect but spare intuition; they used the same language without speaking; and they adored each other free of the need for reassurance…in time Sargent and his sister grew into one person.” As I mentioned last time, neither ever married and there was a lot of speculation about John’s sexuality, and none about Emily’s. More on that in another newsletter, maybe.

“Her temperament was a sturdy contradiction of the sombre wash that covered her appearance: it was brilliant sparkling color. Emily never really believed she had been handed less than anyone else.”

About Emily in midlife, Olson wrote: “She paid careful attention to her toilette, neatly dressing her dark brown hair which was beginning to lighten with the first suggestion of gray. She wore sober, well-made costumes of the best made stuffs, never breaching the fashions suitable for a spinster. Her habits were precise and regular, befitting one who knew as much about respectability as loneliness….(She had) a spirited, delicate intelligence, capable of profound sensitivity and very, very lively humor. She told stories well…Her temperament was a sturdy contradiction of the sombre wash that covered her appearance: it was brilliant sparkling color. Emily never really believed she had been handed less than anyone else.”2 Olson has a strange way with words, but I love that phrase “brilliant sparkling color” about her temperament.

Three novels about sisters to a famous person

In the vein of Emily Sargent, here are three novels about sisters in the shadow of a famous artist/writer/scientist:

The Stargazer’s Sister, Carrie Brown. Lyrical novel about Caroline Herschel,sister of the 18th-C. astronomer and composer William Herschel.

Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper, Harriet Scott Chessman. Beautiful short novel from the perspective of Mary Cassatt’s sister Lydia, who’s dying of kidney disease. Episodic, letters, journals. (2001, sadly out of print.)

The Other Alcott, Elise Hooper. The story of May Alcott, Louisa May Alcott’s youngest sister and the model for Amy March in Little Women, and her years in Paris when she studied painting, and married an Englishman. (This one leans more commercial.)

Your thoughts on favorite books of 2023

Thank you for all your comments, emails, and even a card noting your favorite books (and a few non-faves)! Here’s some of what you loved in 2023:

The title you brought up the most:

Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead (which wasn’t on my list; I still haven’t finished it!),

followed closely by these novels:

Abraham Veghese’s Covenant of Water, Ann Patchet't’s Tom Lake, Ann Napolitano’s Hello Beautiful, Rebecca Makkai’s I Have Some Questions for You, Caroline O’Donoghue’s The Rachel Incident, and Alice Winn’s In Memoriam.

And multiple votes for:

Garbielle Zevin’s Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow and In Love, Amy Bloom’s memoir about her husband’s decline and death from Alzheimer’s, and Hana Halperin’s I Could Live Here Forever.

Less known but intriguing favorites:

The Children’s Bach, Helen Garner, The Anniversary, Stephanie Bishop.

Comic fiction:

Stephen Rowley’s The Celebrants.

Also more Irish picks:

Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting, Donal Ryan’s The Queen of Dirt Island, and Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song.

And last, hyped books that were not so loved by some of you:

Maggie Smith, You Could Make This Place Beautiful, The Guest, Emma Cline, and Little Monsters, Adrienne Brodeur.

Let me know what you’re reading! I’m in the middle of Percival Everett’s forthcoming novel James, a reworking of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim (pub date 3/19/24). It’s a knockout. And for nonfiction, I’m reading Sarah McCammon’s forthcoming memoir The Exvangelicals.

Stanley Olson, John Singer Sargent: His Portrait, St. Martin’s, 1986.

ibid.

Very much enjoyed reading more about Emily Sargent, thank you!

As for reading in 2023 I loved rediscovering Phillippa Gregory's Plantagenet novels, especially The Red Queen which is written from the perspective of a really rather horrible woman that you can't help rooting for! Also I finally read Artemisia by Anna Banti which was written in the 1940s about Artemisia Gentileschi, a really fascinating Baroque painter that I'm sure you'll have heard of. It was a really strange and memorable book, with a great backstory woven into the book itself. I'd love to know if anyone else has read it. Keep writing!

Any chance you’d share your Sargent novel? He’s always been a favorite of mine. The MFA exhibit was a highlight of my winter! I would have loved to have you as my guide with all of your insider information! Thank you for sharing about both Sargents in these two posts. I enjoyed every word!